Tommaso Motti: The Rebel Tailor Bridging the Past and Future of Fashion

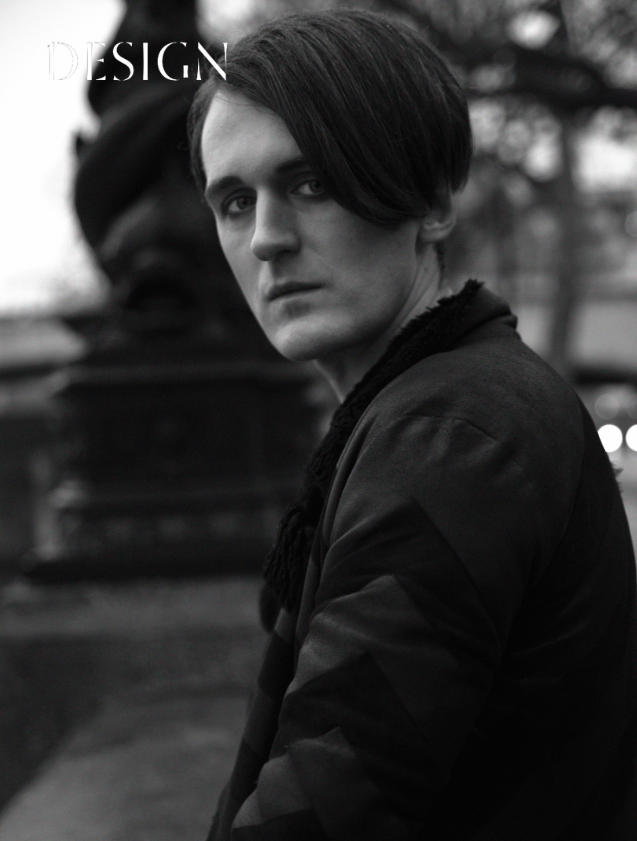

Photography by Serena Gallorini

In a small Milanese studio, where bolts of fabric and broken sewing needles tell the story of relentless experimentation, Tommaso is crafting more than garments—he’s weaving a manifesto. The young designer, who moved to Milan six years ago with little more than ambition and a sewing machine, is on a mission to redefine Italian fashion. His work is striking: oversized puffer jackets stitched from dozens of pieces, alien-like silhouettes that challenge the human form, and intricate details that quietly suggest deeper narratives.

For Tommaso, fashion is a vessel for both preservation and provocation. “Italy has such an incredible tradition of craftsmanship,” he says, reflecting on his heritage. “But I worry that tradition risks becoming a form of gatekeeping.” He describes an industry dominated by legacy brands, their names synonymous with luxury and excellence. Yet, for Tommaso, these icons of the past can feel like barriers to innovation. “I want to honor our artisans by incorporating their expertise into something entirely new,” he explains. “Tradition should be a springboard, not a tether.”

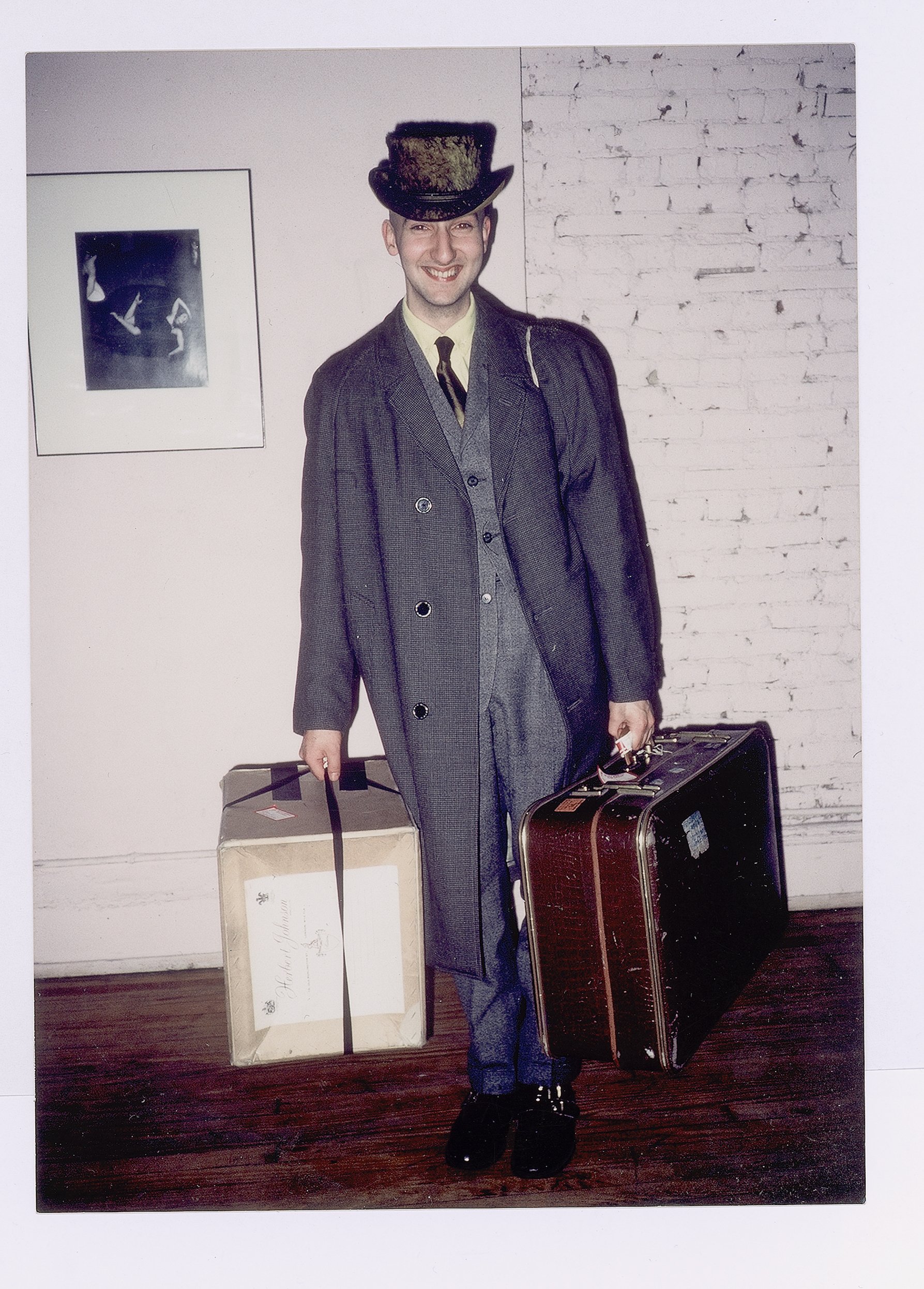

Photography by Asia Michelazzo

Resilience in the Threadwork

If there is one word that defines Tommaso, it’s resilience. His journey to becoming a designer is stitched with late nights, failed experiments, and a refusal to quit. “I moved here with big dreams,” he recalls, “but the reality was grueling.” One of his signature pieces—a massive puffer jacket constructed from 30 unique sections—tells the story of his determination. “I sewed it on a regular machine, breaking hundreds of needles in the process. That jacket is my resilience in physical form.”

This resilience also shapes his worldview. In a society driven by speed and disposability, Tommaso pushes back. “Fashion reflects the zeitgeist,” he says, “but I feel rebellious towards today’s culture. We’ve lost touch with what truly matters—love, nature, and connection. My work is about rediscovering those values.”

Photography by Serena Gallorini

The Alien Among Us

Tommaso’s designs often feel otherworldly—fitting for a creator who draws inspiration from the cosmos. “My past collections are clearly influenced by aliens,” he admits, smiling. Oversized hoods resemble elongated skulls, while his exaggerated volumes feel as if they belong to an ancient civilization from a distant galaxy. These extraterrestrial aesthetics aren’t just about visuals; they carry a story.

“If my designs were a storybook, the central characters would be ancient beings who come to a collapsing planet to teach love and mutual respect,” Tommaso says. This narrative infuses his work, from the names of his pieces to hidden symbols sewn into their padding. For Tommaso, these touches are more than decorative—they’re a way to connect the wearer with the garment on a deeper level.

Timelessness in an Age of Impermanence

Tommaso is the first to admit that timelessness feels elusive in today’s fast-paced world. “Even great ideas last only a day now,” he muses. Yet, he is undeterred. By focusing on craftsmanship and innovation, he hopes to create garments that linger in memory. “Timelessness comes from shocking innovation—something truly groundbreaking,” he says. His current obsession is padding, a recurring element in his work, which he uses to explore texture and form in new ways.

Tommaso’s fascination with permanence extends beyond fashion. Asked about his dream collaboration, he doesn’t hesitate: “A marble sculptor,” he says. The idea is audacious: a hand-carved marble puffer jacket that merges the precision of sculpture with the fluidity of fabric. “It’s about connecting the past with the future,” he explains, “blending traditional techniques with modern design.”

Soul in the Stitching

In an industry dominated by mass production and fast fashion, Tommaso’s process is deeply personal. “I make every piece myself,” he says. “There’s a part of me in every garment.” This connection is palpable. His designs often feature subtle, symbolic details—stitching patterns believed to evoke positive energy. “It’s a small gesture,” he says, “but it connects the garment to the wearer in a meaningful way.”

Looking Forward

For Tommaso, the future of fashion isn’t just about what we wear—it’s about how we live. He envisions a world where garments tell stories, inspire reflection, and foster connections. “Beautiful clothing has lost its true value in this age of excess,” he laments. Yet, his work is a quiet rebellion against that excess, a reminder that creativity flourishes in restraint.

As our conversation winds down, Tommaso reflects on the lessons he’s learned from adversity. “Failure only happens when you give up,” he says. “Hard work is my greatest asset.” In his Milan studio, surrounded by fabric scraps and the echoes of broken needles, it’s clear that Tommaso Motti is just getting started.

Written by Oona Chanel

Designer Tommaso Motti

Fashion Editor Jessica Iorio

Photography by Serena Gallorini & Asia Michelazzo

Sons of Man

OONA: “Italy has a rich tradition of craftsmanship and artistry. How does your Italian heritage shape not only your design philosophy but also your worldview as a creator? How do you transform the weight of tradition into a springboard for innovation, rather than a tether?”

TOMMASO: Italy is clearly known for its tradition and I personally met many artisanal that have an incredible knowledge that I’m afraid it’s gonna be lost in the future. My vision is to preserve that expertise by incorporating it into my forward-thinking creations, forging a tradition that looks boldly to the future. Many of the Italian brands that we all know are symbols of excellence all over the world and they’re the ones who created the tradition. I hope the future allows more room for new brands and designers. Otherwise, tradition risks becoming a form of gatekeeping—if it hasn’t already.

OONA: “Fashion mirrors the zeitgeist. Do you see your work as a reflection of today’s cultural soul, a rebellion against it, or perhaps a dream of what could be? How do your creations speak to the collective consciousness?”

I feel pretty rebellious towards todays society to be honest, both ethically and economically. I’m fascinated by ancient traditions and civilization because back then it was more understood that what the humans really needed was just love and nature. In this capitalistic world, I often feel like a fish out of water, still searching for my own sense of balance.

Especially because what I do is just purely driven by passion and willingness to spread positive and interesting themes hidden in my creations. My hope is to spark curiosity in others, encouraging them to see the world from a different perspective.

3. If you were to design an outfit to embody a single emotion—joy, longing, resilience—what emotion would you choose, and how would you distill its essence into fabric, texture, and form?

I think that resilience might be the best one for me, I moved to Milan 6 years ago to chase this dream, went to university for 1 year and then spent the other 5 years working day and night trying to affine my craft and create clothes more and more complex to express myself.

Resilience to me looks like a huge puffer made by 30 different puffed pieces sewn with a normal sewing machines, breaking needles and thread 100 times, this pretty much embodies what I went through

4. As a designer, you exist between the fleeting pulse of trends and the enduring power of timelessness. How do you navigate this liminal space, and what does “timeless” mean to you in an age of impermanence?

Honestly I don’t get too stressed about this, when I create something it often comes in a blink of an eye, I usually say that I take ideas from the ether, the highest and purest part of the earth atmosphere.

I don’t want to look too much into everyone’s new collection, I’m trying to build the foundation now and my key points are padding and exaggerated volumes, often alien inspired.

Now that everything is so fast and even great ideas last for one day it’s difficult to define what timeless really means, one of my future goals is to try to create a new kind of garment that could be remembered. I believe that only shocking innovation,something both groundbreaking and universally useful,has the potential to achieve timelessness in this era.

5. Creativity often flourishes in the face of adversity. Can you share a moment where failure or an unexpected challenge unlocked a new layer of your artistry or deepened your perspective as a designer?

I’ve always tried to put myself in face of adversity, setting personal challenges that seemed stupid to most of my friends. Yet, these challenges helped me gain strength and a deeper awareness of my capabilities.

Over the past five hard years I’ve always tried to create as much as possible, driven by curiosity and pushed by the belief that failure only occurs when you give up on your dreams.

Working as much as I can has always been my only asset in this saturated market.

6. If your designs were a storybook, who would be the central character, and what universal truth or lesson would their journey reveal? How do you infuse this narrative into the textures, patterns, and silhouettes you create?

My past collections are clearly inspired by aliens, puffer jacket with massive elongated hoods evoke the shapes of alien skulls. If my designs were a storybook, the central characters would be an ancient god-like civilization arriving on a new planet near the collapse to teach them new technologies and help them flourish basing life on love and mutual respect and taking out all the wickedness.

I imagine these otherworldly beings dressed entirely in my silhouettes.

I infused this narrative in some of the pieces either with symbols or by naming products in certain ways

7. In an era dominated by fast fashion and disposability, how do you infuse your work with soul? How do you create garments that foster a profound connection between the wearer and the craft itself?

Since I personally craft every piece there’s some Tommaso Motti in each one of them.

I’m strongly against fast fashion and mass production sonceboth perfectly reflects todays capitalistic society. Beautiful clothing have almost lost its true value in this era of excess and I often find myself questioning where we’re headed.

Besides creating my pieces I often include some small symbolic details, stitched in the padding pattern, that are believed to evoke positive energies around the people who’ll wear it. It’s a subtle but meaningful way to connect with the wearer and add a layer of intention to each creation

8. If you could collaborate with one non-fashion artist—whether a filmmaker, musician, or painter—who would you choose, and what universal theme or emotional truth would your partnership explore? How would this interdisciplinary dialogue shape your work?

I would love to collaborate with a marble sculpture to create a unique marble puffer patiently crafted by hand, like my creations.

I m deeply fascinated by sculpture because it requires a lot of precision and dedication, qualities that resonate closely with what sewing represents for me.

The universal truth would be exploring the connection between past and future, blending traditional art techniques with modern a modern innovative design for the puffer jacket.

Interview by Oona Chanel

Designer Patrick P Yee

Photography by Sons of Man

A Confluence of Fashion and Technology

A Confluence of Fashion and Technology

In the evolving landscape of contemporary fashion, where traditional craftsmanship and modern technology increasingly intersect, SCRY emerges as a distinctive force. Established in 2020 by Zixiong Wei and Olivia Cheng, SCRY seeks to transcend the conventional fashion model by positioning itself as a laboratory that merges sartorial artistry with technological innovation. The brand's name, "SCRY," derived from Zixiong's Instagram handle @scccccry, reflects its ethos of anticipating and shaping future fashion trends through a deliberate integration of creativity and sustainability. SCRY’s approach to design and production is deeply rooted in technological advancements. The company’s exploration of additive manufacturing and digital design began in 2018, culminating in the release of their first prototype two years later. This process involved extensive iterations and refinements, each progressively aligning with their vision. Today, the 'Digital Embryo' framework enables SCRY to streamline production significantly, reducing the time from concept to creation to just three days. The printing process itself, taking under 1.5 hours per shoe, highlights SCRY’s commitment to both efficiency and innovation. Collaboration is integral to SCRY’s strategy. The brand has partnered with prominent designers and labels such as Iris van Herpen, Heliot Emil, Dion Lee, Sankuanz, and Annakiki. These collaborations, featured at major fashion weeks in Paris, Milan, and New York, emphasize SCRY’s engagement with the intersections of fashion, art, and technology.

A Dialogue with the Founders

In a discussion, SCRY’s founders, Zixiong Wei and Olivia Cheng, reflected on their journey and future directions. "Our exploration began with a fundamental question: “How can technology transform fashion?" Zixiong explains. "The path was complex, but through iterative experimentation, we developed a process that integratesadvanced manufacturing with digital design, allowing us to innovate continuously. "Olivia Cheng adds, "Our choice of materials is central to our design philosophy. We use a specialized polymer that addresses the functional requirements of various shoe components in a single print. This approach enhances both durability and comfort while ensuring full recyclability. Our commitment extends to minimizing waste and promoting sustainability throughout our operations." While SCRY’s emphasis on rapid, on-demand production and recyclable materials is noteworthy, it is essential to approach claims of sustainability with caution. The fashion industry, by its very nature, involves significant resource consumption and environmental impact. The assertion of sustainability in production processes can sometimes mask the broader, systemic challenges that remain unaddressed. While SCRY’s innovations in efficiency and material use are commendable, true sustainability requires a more comprehensive reevaluation of fashion's impact on the environment. SCRY’s approach may offer a progressive model for integrating technology and design, but it also prompts a critical examination of the limits and real implications of claiming sustainability in a fundamentally resource-intensive industry.

CREDITS

Interview by Oona Chanel

Pictures by SCRY and Kunliuu

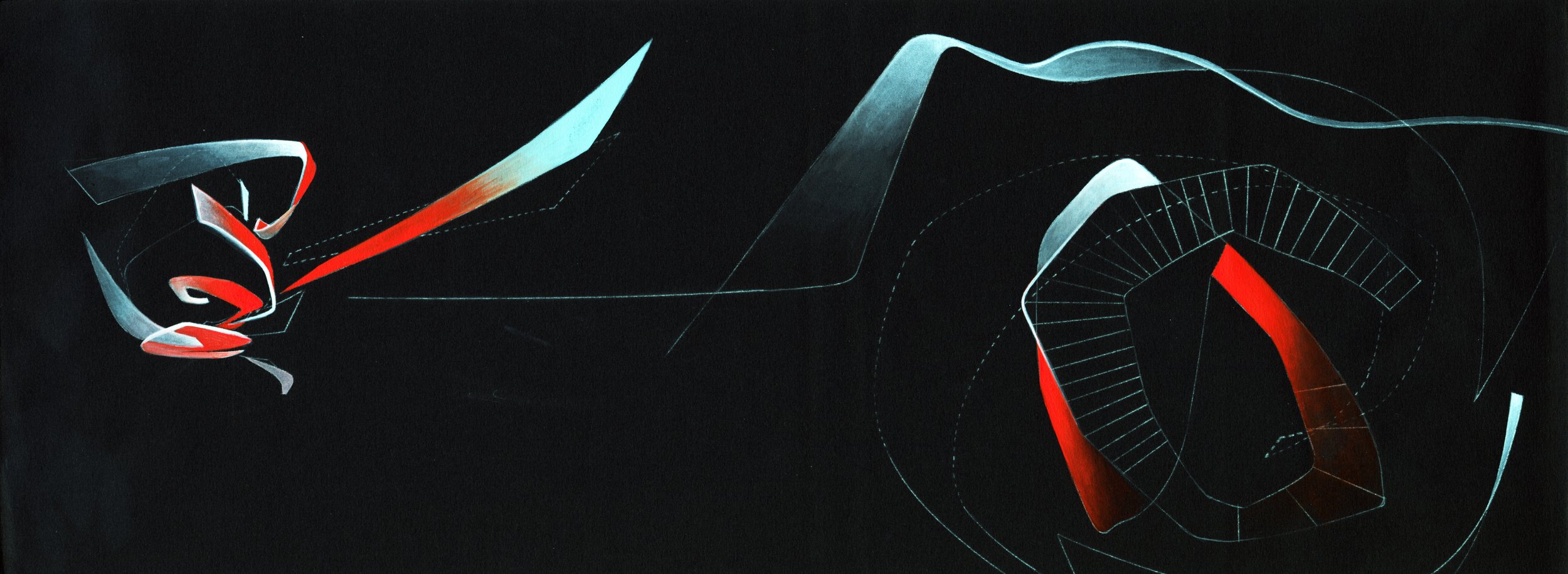

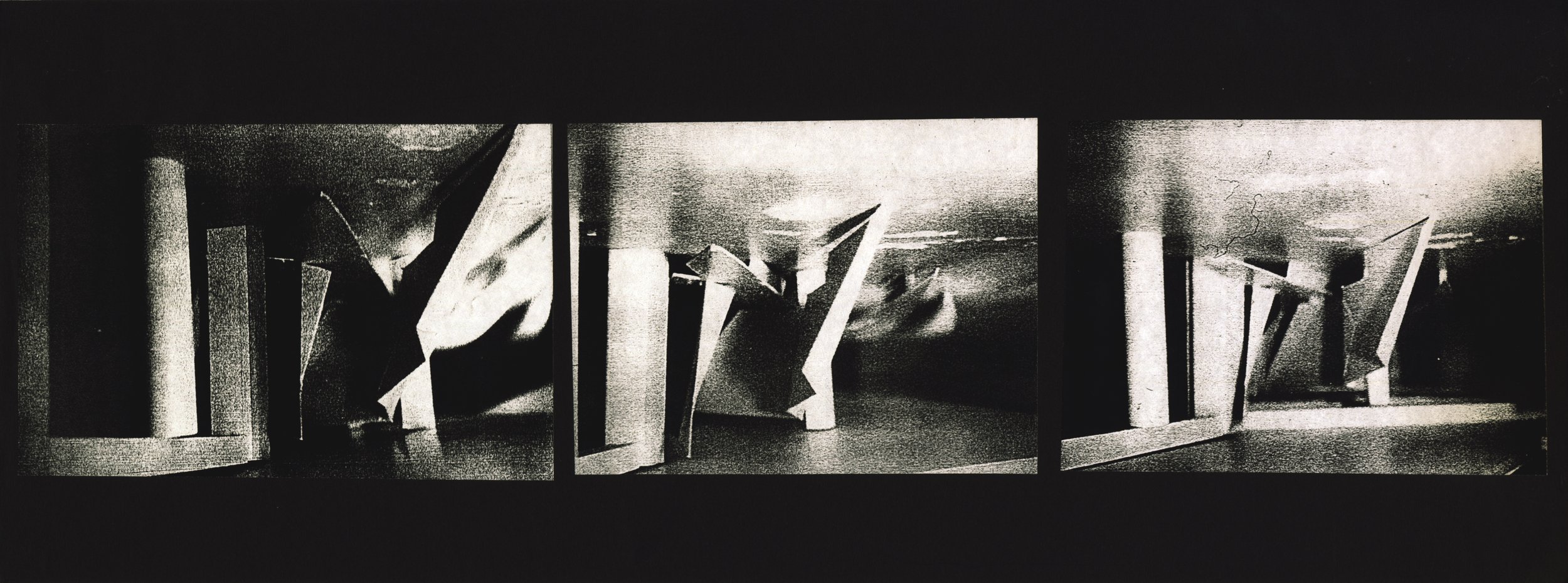

Moonsoon: Zaha Hadid’s First Major Completed Work Abroad

Dame Zaha Hadid is undoubtedly one of the world's most-known architects. And while her prominence is predominantly rooted in architecture through internationally acclaimed works, such as Al Janou Stadium for the 2022 World Cup, Dubai Opera House and London Aquatics Centre, her first completed international commission was an interior design project in Sapporo, Japan. Based on a series of previously unrealised works in Japan, The Moonsoon Bar and Restaurant was commissioned by Michihiro Kuzuwa of JASMAC in 1989 and was completed in 1990. Influenced by everything from the works of Alexander Calder to photocopies of orange peels, the interior acted as an eclectic visceral representation of hybridity and playfulness. But most importantly, this project laid the foundation for design sensibilities seen in Hadid’s later work. Held until 22 July 2023 at The Zaha Hadid Foundation in London, Zaha’s Moonsoon: An Interior in Japan exhibition gave Author a chance to sit down with its curator Johan Deurell. We touched on the significance of the Moonsoon work in the wider Zaha Hadid canon, the prevalent design elements, and the influences behind this project, as well as her unique ability to work across several disciplines.

“Zaha was such a polymath. She could have ended up doing any kind of creative [work], it just happened to be architecture.”

Philip: What's your background in terms of curating exhibitions?

Johan – After graduating with my MA in History of Design from the Royal College of Art, I worked as a freelance art critic and curator, as well as an associate lecturer at Central Saint Martins for a number of years. However, in early 2018, I joined the Röhhska Museum of Design and Craft in Gothenburg where I worked for four and a half years and curated several shows. When I joined, we did a whole rebranding and revisioning project for the museum; I wanted to join because it was kind of a traditional museum with a lot of potential.

Philip: I suppose it was an opportunity to implement your vision within the wider framework?

Johan – It was exactly that. The director of the museum, Nina Due, really wanted it to be a Contemporary Design Museum [while] also engaging with critical dialogues in the field and making it a bit more relevant. I think was also about my take on design. I'm more interested in what people call critical design or conceptual design rather than standard product design.

Philip: I'm quite curious, how did the relationship with Röhhska then transform into working for the Zaha Hadid Foundation?

Johan – I was excited about the Foundation because it's quite nice to join a completely new organisation. You have a sense of shaping it.

Philip: Yes, I can see a theme there — you want to work with and implement new ideas while shaping and taking them in a certain direction.

Johan – Exactly. With an archive-based show like Moonsoon, that's one part of it. I wouldn't say that fits into the kind of curatorial projects I have done in the past because they've all been linked to current political issues, whereas this is about design in a historical context – the Japanese Bubble Economy. The contemporary programme we’re launching in the future is very much more typical for my curating as it engages with ideas of hybridity, exchange and the built environment.

Philip: My question to you is: Why Moonsoon? What was the impetus to focus on this particular work?

Johan – There were several reasons. I was attracted to it on a purely visual basis. But I think it's important [for it] to be studied as part of the Zaha Hadid canon because it's her first major interior and the first project to be completed outside of the UK. It's the first time we get a sense of what a Zaha building might have looked like. Before this, she had only done paper-based architectural projects with the most publicised one being the Peak Project in Hong Kong from ‘83, exhibited at the Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition in MoMA in ‘88. In those earlier projects, Zaha Hadid Architects developed design strategies such as the layering or warping of shapes, the oblique nature of those shapes, and the embrace of all angles — those ideas established the early design language for the practice. I see Moonsoon as a blueprint for later architectural projects.

Philip: Were the interiors, especially the furniture, made by Zaha Hadid Architects or were they commissioned externally?

Johan – They were made by Zaha Hadid Architects. It's a practice with several people contributing, although in the ‘80s there weren't that many. Michael Wolfson, who was employed by Zaha, designed the sofas that were part of the seating landscape, but several people contributed to the various elements of the project. This included the interior, the architectural elements, and interventions such as the orange peel vortex and the black swirl going through the two floors.

Philip: What were some of the founding principles she based this work on?

Johan – The Kita Club building, built by Dan Sekkei Architects and Mitsuru Kaneko in the late ‘80s, contained a sort of dome which Zaha didn't like. So the orange peel was a design intervention. The vortex was a central theme in the design of the building. I saw it as a leading visual key, connecting all the objects and the exhibition. I interviewed the various architects who worked on the project, and they kept saying, “You need to find a Post-it note or sketch or something with little doodles.” In this case, it turned out to be a sheet with an Arabic letter. I wanted Marwan [Kaabour] to work on this as a graphic designer as I wanted to construct a slideshow to link it with that shape. He speaks Arabic and says that this swirly shape reflected a stylized version of the letter H in Zaha. But there were also a lot of other interesting references: Photocopies of books, orange peels in the photocopier, and works by Alexander Calder — loads of different works that had a similar shape.

Philip: Yes, it’s interesting you mention Calder because when you look at her work, you see the likes of Malevich, Calder, and Lissitzky having a huge influence on her.

Johan – Yeah, I agree. One of the reference images that we found was the Aula Magna of the Central University of Venezuela, designed by Alexander Calder. It has these typical Calder shapes for absorbing sound in the ceiling. And if you look at them — the sofa, the sofa’s backrest, and the tables — they look like elements from Calder’s “Mobile.” Her design language is heavily influenced by Malevich and the Russian Constructivists. In the early projects, she sort of translated that into architectural design strategies. And Zaha, as an architect, was very visual. And you see all these visual sources and how they come together.

Philip: Yes, she was incredibly visual and influenced by fashion in her design practice, especially the likes of Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake. Would you be able to tell me more about that?

Johan – That's a research project we are going to undertake in the future. We have a large fashion collection in our archive, including clothes, bags, shoes, and jewellery by several big designers. We know that fashion was important to her; she paid a great deal of attention to it. Zaha made her own clothes when she was a student. Wolfson told me that Zaha was such a polymath, she could have ended up doing any kind of creative [work], it just happened to be architecture. I found some evidence of how fashion influenced her work, which I haven't had time to research properly. She did this project for Pet Shop Boys and designed the sets for their world tour in 1999. There’s a mood board for that project that contained some pleated Issey Miyake pieces.

Philip: Zaha Hadid had her fingers in almost every possible pie; she was an architect, a designer, and a painter. Will the foundation have a look at Hadid's larger body of work at some point?

Johan – We will. And that’s also why I found the prospect of [working for] this foundation interesting because I'm interested in interdisciplinary practices. What makes her so interesting is that she moved and operated within these fields. But it’s also about connecting the dots between her work within these different disciplines.

Philip: These are the type of things the foundation is such a vast source for. You have such a large archive to work with.

Johan – I’m super excited about the fashion-slash-Zaha relationship and would love to make that into a separate, large-scale exhibition for an international tour in a couple of years. It is interesting to depart from our archive to look at ways in which fashion and architecture intersect and feed into one another.

CREDITS

Interview by Philip Livchitz

Pictures by Zuzanna Blur

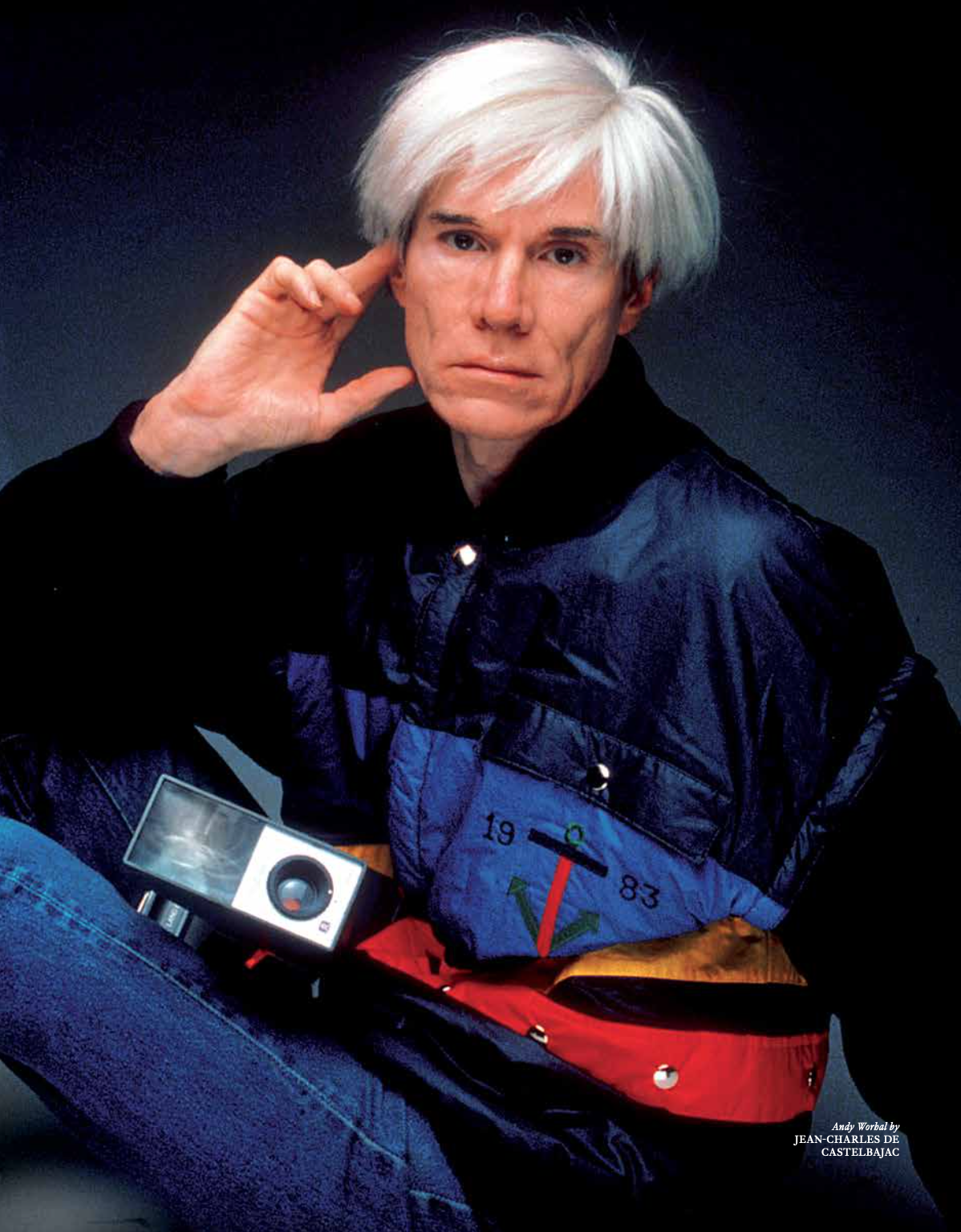

Wilder Than You Think JEAN-CHARLES DE CASTELBAJAC

There are few renaissance-spirited creative souls among us, with a back catalogue of such singularly impactful cultural resonance, who can hold a candle to the work of legendary provocateur, artist, and rogue bon vivant Jean-Charles De Castelbajac. The rebel son of an aristocratic French lineage, he has set the world alight for 40 years with explosive art and fashion marbled with a distinct aesthetic that has become synonymous with positivity, radical self-expression, and celebratory creative freedom. The singular penchant he has for transforming what could arguably be considered as the absurd into the iconic, such as his divisive pieces inspired by Snoopy and Kermit the Frog, and has witnessed collaborations with everyone from Basquiat, Cindy Sherman, and Keith Haring, to Andy Warhol, and far and beyond. Infamously, he designed offbeat ecclesiastical robes for Pope John Paul II’s visit to Paris in the 90s, and his coterie of some 5,000 priests. AUTHOR took time out in Paris with the now 68-year-old Jean-Charles to mine the core of what drives him philosophically, and find out what he believes most pertinent to the challenges of the creative, having lived through, and impacted, the constantly ricocheting transformation of culture over the years, as brilliantly captured in his recent non-linear memoir Fashion, Art & Rock‘n’Roll. AUTHOR presents an intimate snapshot of a man whose commitment to radical intervention, political fashion, and the art of collaboration keeps him leagues ahead of the curve, and find out why fashion is an industry full of beautiful ghosts....

AUTHOR: Why has rock‘n’roll been so important to you over the years?

Jean-charles — Before fashion, there is always rock’n’roll, and all through my life, it has run like a river. I remember going to a rock concert of a man called Vince Taylor when I was 17 years old. He was in this cheap club, and on-stage with him was a blonde guy, almost like an angel, who was just there to beat the tambourine; that was his only job. I instantly saw this other kind of beauty; something about attitude, accidents and some kind of wonder. When I met Malcolm McLaren in 1972, it was the same kind of wonder. All through my destiny, rock‘n’roll has been like a wave and fuel to an amazing quest, a quest to see things beyond the mirror, and to get beyond what Malcolm used to call the karaoke society.

AUTHOR: Malcolm and the punk movement had a very distinct mainstream to kick against, how can we retain that spirit in the age of multiple convergent cultural streams?

Jean-charles — I think that, as you say, subculture was linked to a mainstream that was totally parallel, where everything was about a quest of knowledge and intelligence, but this has been abolished by the digital age. Now, it is not about how to create a counter culture, but is about creating an invisible parallel culture. It’s about finding a way to put your own mark on culture as a group of people thinking the same way. In that way, my eternal quest has never changed. The essential quest of life is to build a soulful and intellectual family; people you can go on a creative adventure with. The energy of creativity can play a fundamental role in proposing something different; in proposing something that is not just to escape the reality, but to really build something new.

AUTHOR: For you, who are the most important people currently working towards forwarding cultural expression and resistance?

Jean-charles — The artists I am interested in now, like Kate Tempest or Robert Montgomery, they really see this need to speak about the beauty, and also the terrible realities of now, and how to come to an age of compassion. As artists, we cannot just be there to hear the testimony of cowards. We have to plant the seeds of the renaissance. It’s about creating a kind of poetic virus; it’s about getting into the flow of something. I remember seeing Suicide perform and Alan Vega singing ‘Dream Baby Dream’. That was like a disease poetry; a disease that got inside your soul, and what has remained about that is still there in the new kind of resistance. It’s like a virus of poetry in the system.

AUTHOR: Do you think we are entering quite a dark period in our collective history?

Jean-charles — I do feel that now people are looking for something else, because we feel this shadow of darkness. I lived through the era of the Vietnam War and the darker time of the 80s, when I lost a lot of friends, and then, of course, the 90s, which was a tsunami of marketing and money. The consequence of that decade is that we now have an age of darkness and inequality, so it is the role of every artist today to fight for something, and to speak out in such a time of dystopia.

AUTHOR: How can we find a sense of beauty in such an era?

Jean-charles — There is a poetic definition of beauty that is linked to the soul and linked to something invisible and, in a sense, linked to a kind of harmony. But it’s like we are living in a post-innocence time right now, where even what we think of as having beauty, like the sunset or sunrise, or the drop of dew on a flower, cannot help us forget what is happening in the world any more. I still have hope in humanity though. I see now that the political conscience is waking up, in a sense, so that everything happening is inspiration for artists. Everything is a total paradox, and in that way the dark side allows us to participate.

AUTHOR: Have you always been driven by a desire to rebel?

Jean-charles — It was always about rebellion all through my life. When I was a little boy, I went to boarding school, and that was very much about order and discipline. My only route for resistance was to disrupt the order and always have something different, or seemingly accidental, about my uniform. I was always punished for that, but it was, for me, a way of saying: I don’t want to be like everybody else. I love that. I don’t like harmony so much; I like discord. I love to see my life that way, as a sport of cadáver exquisito. I want to begin something and then someone else will continue it; there is a beauty in that disharmony. The most exciting moments in my life are when I do things with other artists; when I can share. I used to do that when working with Keith Haring and Basqiuat, to begin to draw a line that they would finish.

AUTHOR: Where would you say that positivity and drive to collaborate comes from?

Jean-charles — Hope and humour have always been my natural reaction to disaster and my shield and resistance in the most difficult moments. I have realised that my work has been like a therapy for some people, to help them to reveal themselves. When I see a man I love like Tinie Tempah, and how much my world has touched him, it is a magical thing for me. Keith Haring was inspirational like that. He was the most generous man I have ever met in my life. There was never any greed or jealousy around him. He never cared how much a collector would buy work for because he wanted to make his work for everyone, and he was so fast, so instinctive and musical in the way he did things. Malcolm was similar, but with more of an intellectual point of view, more on political concerns.

AUTHOR: How do those concerns play out in the arena of fashion?

Jean-charles — The catwalk is always kind of linked to a discovery of political concerns, so all of my clothes and shows have a political origin, and it’s always telling a story. Clothes are the most amazing thing because they are the most intimate link to the human, and it is the most important medium for art today because everybody looks at it. Fashion is not just for an elite; fashion has a democratic role and it’s a very good tool for democracy because it’s the beginning of individuality. I never created fashion for any trend, but more, as Malcolm would say, as a manifesto. A manifesto of what I think of my times and, in a sense, what I think about ghosts, because fashion is about ghosts. When I go into a vintage store, I feel sometimes I am in the middle of a temple of ghosts. Surrounded by all these people who have worn these clothes, who have made love in these clothes...

AUTHOR: That’s beautiful... In terms of ghosts, what is your personal opinion of death and afterlife – what remains of us when we are gone, and in what way?

Jean-charles — My feeling is that already I am the link to all my ancestors, and I am the servant of all the people that I love and have loved. I carry them all with me, and they carry me in them. Tomorrow I will be in you, in my sons, in others, and I will be forever there. It’s all about how we have been living our lives. I don’t believe in God, but I believe in the soul; in the idea to always be on the side of the people I have loved... I don’t know in which form. Perhaps as an angel, or a blow on the cheek, or in some kind of light falling into the room. I don’t know about the form, but I do know I will be the same soul I am today, and whatever form I am will then be with many people.

CREDITS

BY JOHN-PAUL PRYOR

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEAN-CHARLES DE CASTELBAJAC

PORTRAIT BY LINDA BUJOLI

Euphoric Creativity with Satoshi Kondo

“I believe that inspiration is something serendipitous, and in that sense, not something that can be forced.”

It’s only been a couple of years since Issey Miyake had a change of creative direction in the womenswear division. That kind of responsibility often comes with great expectations, but not only did Satoshi Kondo meet them, he also raised the bar. Through movement, a signature aspect of Issey Miyake, the young designer, was able to respect the house’s codes and maintain the brand’s DNA. However, he elevated it with interactive performance art, such as dance and lived drawing, whether through his physical shows or presentations. His artistic vision and multi-purposed clothing items bring newness not only to the Japanese brand but to the industry as one collection after another Kondo has captured our curiosity. As all art form is subjective, his shows leave us with a topic to reflect on often about positivity and oneness.

“I believe that inspiration is something serendipitous, and in that sense, not something that can be forced.”

In a conversation with AUTHOR, the young designer shares his passion for the craft and the shifting mindset that must take place when presenting collections nowadays. We also talk about the industry’s future, inspiration, and innate talent for material sourcing.

What was the most enjoyable part of creating this collection?

My favorite part of creating a collection happens when my team and I are about to find a way to translate our abstract idea or concept into a clothing form. It is a transition from an idea to its realization, including the brainstorming and the research that leads to this feeling that I enjoy the most. In that sense, I also enjoy taking a piece of fabric and working with its material qualities to make it into a garment. For example, for the FLUIDITY LOOP series, I engaged in the process of looking at the fabric knit in a spiral shape and imagining how to turn it into a garment by making use of its character and texture. For the LINK RINGS series, I began with the notion of creating apparel by connecting circles and then continued with the design process of realizing that idea into a series of circular, hand-pleated fabrics.

What is your take on fashion moving forward with digital aspects?

I feel that the prevalence of digital shows has made collections more accessible. Now a collection can reach its audience at a speed and a breadth that the industry has never experienced. Because of this new form of communication, more people worldwide get to see a collection and get to see it quicker, including those who didn’t have the means or the interest to see a fashion show before.

For this collection, we worked with the video director, Yuichi Kodama, to explore the potential of a video in relation to the collection theme—visual components that can only be done digitally. With some deliberate editing and subtle special effects in the video, we were able to convey the sense of descending into the depths of the sea without actually doing a show in the water.

What are the challenges you face when sourcing continual inspiration for collections?

I believe that inspiration is something fortunate, and in that sense, not something that can be forced. For me, finding inspiration is not about thinking about finding inspiration first. I often stay active at work and in life, thereby allowing myself to be in an environment full of creative work while always staying open to new ideas, whatever they may be. To that end, I always expose myself to things I find Interesting, like going to exhibitions at museums.

How important are physical shows for you vs creating a video to present the collection? In terms of presentation format, physical vs digital, as a designer, I always try to adapt to the circumstances and make the most of what is available in a creative way. I think there is something about a collection that only a physical show can convey, and the same can be said about a digital show.

I would like to do a physical show for the following collection if the circumstances allow. Having presented three groups in digital form, I became more interested in the sensations one would feel at a live show/performance: the excitement of attending and being part of a show that only happens once, the firsthand experience of looking at the design and textured qualities of garments, and the warmth of the audience as well as the character of the show space, contributing to the ambiance of the show. Even if a live show like this is filmed and later presented as a video, it still captures the qualities of being life, which differs from a digital presentation that is fully edited and choreographed.

What’s one piece of advice you would like to share with other designers in the industry? As the designer of ISSEY MIYAKE (the women’s collection), I can only speak for my practice at the brand, and I would be grateful if other designers find it applicable and helpful in some way. For me, the most important aspect (and challenge) is our entire and continued engagement with research and development, where we integrate technology and creativity as the basis on which we create original garments for every collection.

Alexandre Vauthier - The Coruscating Couturier

Oona Chanel Unravels What Drives The Classically Trained Designer’s Dedication To His Craft

It’s not hard to see why Alexandre Vauthier is a darling of the fashion industry, exclusive couture clients, and celebrities alike. His designs strike that perfect, almost unattainable balance of being both timeless and refreshing. The silhouettes are intentional but not forced; modern, nearly architectural and staggering in their sharpness, while simultaneously maintaining a classic French allure. Couture is the genesis point, and even his prêt-à-porter collection draws directly upon it. Consequently, Vauthier’s work is embedded with a subtle empathy and one cannot help but understand that he is fundamentally and critically attuned to modern, worldly women. In this extract from our extended interview, Oona and Alexandre discuss the forces that shape his enigmatic designs.

Oona: What does fashion mean to you?

Alexandre- I prefer to speak of style, so it’s fair to say I can’t say what fashion means to me. What disturbs me about fashion is the short period of time that it represents. I prefer to think of my design house as a body of work that will still stay relevant throughout the years. I don’t try and make noise with my clothes. What I do is both sincere and carefully considered, which is why all the girls that I’ve been dressing from the beginning still come back to me quite frequently. My clients are from different cultural backgrounds, but they all gather here at my atelier. Fashion itself is not really important. What is important is how women look wearing these clothes. If my creations become ‘fashion’ after that, even better, but being in fashion is not the essence of the creation.

Oona: What about couture?

Alexandre - Couture is everything to me. It’s the beginning of creation, where there are no budgetary or technical limits. When everything is made by hand, it becomes an intense discussion between the creator and their craftwork, which results in the most beautiful creations in the world. Time is such a luxury for me, but when I have it, I’m able to create something unique. It’s the same way of thinking about jewelry, where time yields the best results. The great bene t of an obsession with couture is that my p rêt-à-porter collection can then bene t from all of that expertise. During these haute couture design trials, we try to expand the concept of luxury, and that then results in a superior quality that’s used in the p rêt-à-porter collection. For example, the embroidery that I’m working with for the couture collection is also used for the prêt-à-porter.

Oona: How important is it to feel inspired?

Alexandre- Having inspiration is everything to me! You have to be inspired. Everything inspires me in life. Our conversation we are having now will inspire me. I am someone that observes others a lot. I’m very precise and I consider the details. I love life and I’m afraid of not having enough time to learn everything. To be able to see everything, to know everything, and at all levels. I’m inspired by the importance of human relations, and how different cultures and friendships interact. Within this, the concept of femininity is seen in many of my creations. Observing how women live and interact, their lives fascinate me, and I’m left inspired by their happiness. I draw my inspiration from all of the above.

Interview by OONA CHANEL

Picture by SYLVIE CASTIONI

Empress of the senses - Betony Vernon

Known chiefly as a creator of transgressive jewelry, the flame-haired

femme-fatale Betony Vernon is also a ‘sexual anthropologist.’

Known chiefly as a creator of transgressive jewellery, the flame-haired femme-fatale Betony Vernon is also a ‘sexual anthropologist.’ Described by Alejandro Jodorowsky as an ‘urban shaman’, and deferred to by some of the most renowned doctors in an evolving eld of sexual wellbeing, her therapeutical work explores what most would consider to be an obvious precept of sado- masochistic practice. While she is not interested in such categorisation, she is convinced that all kinds of sexual pleasure, no matter how one attains it, demand a certain level of dominance and submission. In this excerpt from her extended interview in Author Magazine, the author of The Boudoir Bible:

The Uninhibited Sex Guide for Today speaks to us about the future of human relationships in an increasingly fractured sexual landscape.

“I am public about my conviction that the power of love and spiritual wellbeing are far more potent than anything else, and it is for this reason that love, like pleasure and self-knowledge, are not encouraged by our class structure. In fact, they are traits that are constantly undermined by the establishment. This is because a happy, well-loved and spiritually grounded society makes for a really bad economy.”

“I do not believe in creative or sexual hierarchy because everyone and everything is interdependent. Collaboration is extremely important to everything I am and do. It makes my creative process possible. Sex affects every facet of our lives, physically, politically, socially and spiritually, and sexual behaviour motivates all of my works. Monogamy is just an ideal and its foundations have been shaking since the beginning of the second sexual revolution in the 1960s. Polygamy has been around for a very long time. What interests me the most is polyandry, which is the bond between three or more consensualintimate partners that is headed by a woman, not a man.”

Interview by JOHN-PAUL PRYOR

Picture by RAUL HIGUERA

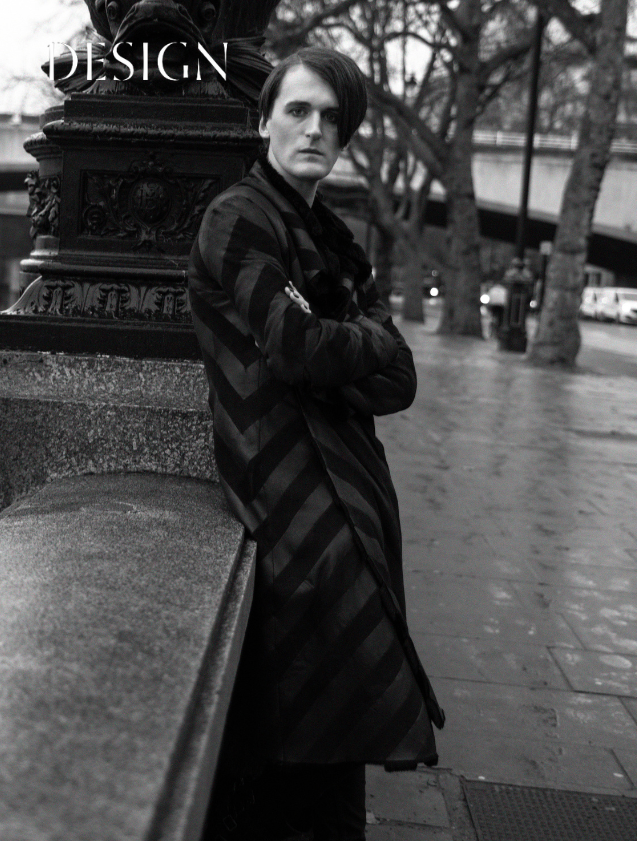

Transcendent Design, Gareth Pugh

Into The Mystic With The Gatekeeper of Alternative Fashion

Gareth Pugh is arguably the most significant avant-garde London- based designer working today. The Central Saint Martins alumni par excellence is the logical successor to Alexander McQueen, also favouring the abstract, gender- fluid, quasi-political representations of extreme individuality over the temptation to succumb to the ever present pressure to create a watered-down fast-fashion line. In this full extract from his interview in the second edition of Author, the ever-modest designer invites us into his East London studio to discuss staying true to your vision and how a concept from Spanish folklore can elevate creatives into a temporal moment of aesthetic perfection.

“We don’t do things as contrived as like, make little season plans and sort of go, ‘This is what we’re going to do!’. It’s much more about breathing it, and feeling what you want to do. It’s about finding those intangible things that give you that moment of clarity; maybe it’s something that you’ve always seen but never really appreciated or something you’ve always known but never quite understood. It’s like looking for the ‘duende’ of Spanish folklore. In one sense, the duende is like a little kind of mythical goblin, but in flamenco, it’s the guitarist or the dancer achieving this trance state, which means having that connection with the audience that transcends emotion. It’s like pure artistry in its finest incarnation, where they’re actually being embodied by something that’s greater than they are, and it’s sort of a vessel to communicate that to the audience. Everybody who creates wants to sort of achieve that, because it’s so fleeting and so temporal, and you always want more of it precisely because it’s not present. I guess you should never really be satisfied with what you do because as someone who wants to make things, if you achieve that nirvana of doing something perfect, if you do actually reach duende and create that perfect thing, then why try and sully that vibe by doing something else? It’s really a sadistic way of working, in that you’re always searching for this thing you know is never going to be quite achievable.

“We don’t make any money from the things we make here but, for me, it’s never really been about making money. It’s about the work and what we put forward, and about the image being the thing that defines you, and having that valued more than however many crappy little mini dresses you sell, or whatever. I feel very connected to that side of things with regard to rolling your sleeves up and doing things because it feels right, rather than thinking ‘how am I going to sell it?’. Fashion feels quite dirty at the moment. It doesn’t feel like it’s got a lot of genuineness about it. I tend to feel some sort of synergy with punk, or an affinity with that idea of doing things yourself. That sort of thing feels very genuine and feels very essential, and I guess it’s a choice to do that. It’s really important for me to maintain that level of investment in what I do. For me, punk is about the amount of effort we put in.”

CREDITS:

Interview by JOHN-PAUL PRYOR

Pictures by Jonathan Mahaut

A droit of style - Donna Karan

The Enduring Design Legend Reveals Why The Feminine Form Is Her Ultimate Inspiration

Has there been a designer more attuned to what women really want–not what brands want to sell them–than Donna Karan? Focused on creating the perfect cut, the designer is a driving force in how the career woman can work her own aesthetic into the everyday, presenting style as an essential, rather than a nice to have, and worshipping the feminine shape instead of flattening curves into submission. Her name is synonymous with chic, cleverly cut pieces, and no modern capsule wardrobe is complete without the inclusion of a Donna Karan wrap skirt. With a New Yorker power stride, she’s left her fingerprints all over consumer fashion history, from surviving and thriving under the notoriously watchful eye of the late Anne Klein, to launching her own namesake line without a safety net, let alone any semblance of a budget. In this extract from our extended interview in Author, she reflects with Pauline Brown, former LVMH exec-turned-Harvard professor, on her childhood and early inspiration.

Pauline: How would you describe your childhood?

Donna -I was a young girl who was probably a little different than the rest. My mom was in fashion, my father was in fashion. In those days it was kind of unusual for your mother to be working, so it felt a little strange living in a community where all the other families were together with the mother staying at home during the day. I loved school, but art really was my passion.

Pauline:Your mom was a model and your father was a tailor. Did their respective careers have an effect on your decision to go into fashion?

Donna -It was the one thing I didn’t want to do. You know, you never want to do for a career what your parents are doing, so the last thing I wanted to do was to be in fashion. I wanted to sing like Barbara Streisand, dance like Martha Graham, and maybe be an illustrator. But fashion designer? Not at all.

Pauline: You failed draping class, which is so funny because to anyone who studies your designs, you are the queen of drapery.

Donna -Yes, I burnt a hole in my dress with an iron just before presenting to Rudy Gernright, and had to go to summer school for draping. And yet, I passionately adore the body and fabric. It talks to me. Draping for me is more artistic, while at school it is more about flat-patterns and creating the garment.

Pauline:You graduate from Parsons and shortly thereafter, you work for the very formidable designer Anne Klein.

Donna -I got a job with Anne when I went for a summer job. I was feeling really nervous, and she says to me, ‘Take a walk’. She thought that I was there for a modelling job, and says that my hips are a little too wide. I showed her my portfolio, and I was hired. My first big job was getting her coffee, pencil sharpening, and everything like that. I was the bottom of the totem pole, and I would sneak around with my head down, so embarrassed. The fashion world was something I was familiar with, but working with Anne Klein was rather difficult. She convinced me not to go back to college at Parsons, so I never graduated. And after nine months of working there, she fired me.

Pauline:Then what happened?

Donna - T he next day, I became an associate designer to Patty Cavalli on Broadway, and Patty immediately took me to Paris. I was 19 years old and a Jewish girl, living on the train tracks in Long Island, and there I am in Paris and Saint-Tropez, my first time in Europe. I was Patty’s only design associate, so I really learned a lot and tried my hand at everything. But still, I wanted to be back on 7th Avenue. It’s hard for people to discuss it, but 7th Avenue is fashion, and Broadway is more mass market. Once I realized this, I called Anne for my job back.

Pauline: Was the interest in going back to Anne because you believed in her vision, or was it just because she was the one person you knew who was still on 7th Avenue?

Donna -My ego was, of course, involved, what with being fired, wanting to prove myself on 7th Avenue, the luxury of the fabrics and all of that. Anne Klein understood women both mentally and physically, which is something I found myself drawn to. Anne was designing for Anne, but she was also designing for her customers. I’ll never forget the one thing that she did when hemlines dropped from one season to another, she kept the exact fabrics of the last season and just made longer skirts to match the jackets her clients already had. I thought, how brilliant it was that she wasn’t just coming up

with the next collection, but also really catering to the consumer’s needs. She was an artist and also a consumer.

Pauline:So, in 1984, you decide with Steven, your late husband, to launch your own brand.

Donna -I felt a desperate need for my own clothes. Personally, I needed a bodysuit, a wrap-tie skirt, little 70s pieces, and I really wanted to do it as a bitty collection for me and my friends. I told my bosses at Anna Klein how I felt, that I wanted to have a go at this little thing, and they basically said to me, ‘you’re fired’. They said, go into your own business and you’ll no longer do Anne Klein. That was really a kind of death for me because I had designed for Anne Klein longer than Anne Klein did. It was really a shock to my system.

“I loved school, but art really was my passion.” – Donna Karen Pauline:What were the biggest challenges in the beginning?

Donna - W e worked in my apartment, and I had all the fabrics delivered there. I didn’t have a sample room or even a design room–we didn’t have anything. I had one girl working with me, and we were just doing sketches, but we were on such a tight budget, and I was not used to being on budgets this tight. So I was counting every single cent that I was spending to create these 70s pieces.

Pauline: What was the thinking behind your own label’s pieces?

Donna -I thought of the woman who was on-the-go, constantly travelling, who was going from day to night and who never has time to go home. I wanted a wardrobe that would take you from day to evening. From relaxation, which is how I start my day with yoga, so that’s how the bodysuit and leggings came into work, and then the wrap-tie skirt. Then it was a blazer, a scarf because I thought scarves were the accent to everything, an evening piece which was the sequinned skirt versus the jersey wrap-tie skirt, and a coat.

Pauline:What’s your style advice for prominent women?

Donna - T o not to be afraid to show off your own form and body. Why can’t we feel like women without being sexual, but by being sensual and comfortable, and really understanding your own body?

What I call accenting the positive, deleting the negative. I don’t think a lot of people realize what accents them, what complements them, and how draping hides a multitude of sins.

CREDITS:

INTERVIEW BY PAULINE BROWN

INTRODUCTION BY MICHAELA WILLIAMS

PICTURE BY DONNA KARAN

The world according to..DEAN & DAN

It all begins with an idea.

Fashion’s favorite siblings share their passions outside of the fashion sphere and explore a few mantras for life...

The identical twin brothers and founders of DSQUARED2 need little introduction in the fashion industry, having gained notoriety for dressing pop’s nest, courting controversy, and creating shows of unparalleled decadence. The dynamic Dean and Dan Catena have been in the game of style provocation for over thirty years, launching their iconic brand only ten years ago and witnessing its stratospheric rise into one of the most innovative and talked about modern labels, revered for sending models wading through inches of mud on the catwalk or introducing muscle cars to the fashion stage. In this extract from their extended interview, we throw a few mantras at the inseparable and eccentric siblings to nd out what inspires them.

Author: Lose an hour in the morning, and you will spend all day looking for it.

Dan - Morning habits? I do an intense workout with my personal trainer as I wake up. I also like to change it up, and try different daily training. Then a good Pilates lesson. Starting the day in this way is always regenerating and so healthy! Try it; you will see how much your daily mood can change!

Dean - The first thing I do every morning has a good breakfast with a latte macchiato and a cigarette. Then, if I listen to music during my breakfast time, I really enjoy my day! Food and music, what else? Nothing better to start your day!

Author: Sports do not build character–they reveal it.

Dean - We love snow and water and we love to do sport in both– snowboarding makes me feel like a child. It is pure adrenaline! This sport is like a brotherly sport for us. Our personal trainers always show us different and secret places to do it. It’s one of the best ways to have fun and relax.

Dan - I prefer summer sports! I am in love with water sports. In the middle of the sea, you can really breathe a sense of freedom– it gives you the ability to push away every lousy thought.

Author: For those who are lost, there will always be cities that feel like home.

Dan - Toronto is my favorite city. It’s multi-cultural and full of creative stimuli from the architectural structures to the lifestyle. There is a former industrial area that I really love called The Junction. That is the most stylish place in the city at the moment. Toronto is definitely synonymous with lovely people, unexpected places, and innovation. It’s the perfect international atmosphere to live in!

Dean - Rio de Janeiro. It’s sunny and smiling–beautiful beaches and funny people; good food, good vibes, and warm! You will never get bored! The Lap district is the best place– there are lovely restaurants and bars, music everywhere, and only native people. It’s the most colorful city in the world, and it definitely matches my personality!

CREDITS

Interview by OONA CHANEL

Picture by Andrew Woffinden

Art of Intention - Stephen Jones

It all begins with an idea.

“I think the only time that fashion ever really makes sense is when it has sociopolitical comment. That’s when it really galvanises people.”

– Stephen Jones

Sir Stephen Jones does not hold the accolade of being the most charming man in fashion for nothing. Ironic, erudite, and genuinely self-effacing, the Liverpool-born milliner with a cheeky glint in his eye has been an unparalleled force in the industry since the 80s, the decade he and his Blitz Kids peers came to define, one gender-bending fashion statement at a time. His vivacious energy and work ethic is nothing short of legendary and his talent ubiquitous. He’s provided uncompromising show-stopping visionary accompaniment to the likes of Galliano, Gaultier, and McQueen, to name check but a handful of the legends he has worked with, and to some of the celebrity sphere’s most groundbreaking artists, such as Grace Jones, Dita Von Teese and his lifelong friend, Boy George. Here, the man who has provided the perfectly balanced ‘cherry on top’ of some of the most iconic fashion moments of all time, tells AUTHOR why a thing of beauty can only be seen in retrospect, how the baton of anti-corporate subcultural identity is being carried forward by a new generation of outsiders, and why pure fashion is an art form so fearsome in its naked form that it can scare the living daylights of you.

AUTHOR: Can you remember any distinctive moments in childhood that set you out on your path in life?

stephen — There are a couple of things. When I was really young, five or six, or something, I used to watch puppet series’ on the TV – this was the era of Fireball XL5 and Thunderbirds – and I remember getting very confused because I felt that the shows were more real than the life that I inhabited with my parents. That was really the first thing. The other thing was that I knew I somehow didn’t fit in. I was at a very traditional boy’s boarding school in Liverpool and I remember buying some platform shoes, which I thought were fantastic and my housemaster saying, ‘Jones, for God’s sake! Take those high heels off!’. And I remember just thinking: ‘you are wrong! This is the way forward!’

AUTHOR: And it was this combination of feeling like an outsider and a penchant for fantasy took you to Saint Martins...

stephen — Well, the third thing was that I realised at Saint Martins that I couldn’t sew! So, I became a tailoring intern at a couture house, and next to the tailoring workroom was the millinery workroom, full of these wonderful older ladies. I transferred from one department to another and, after the first day, I knew this was what I wanted to do more than anything else. Those were three really defining moments. I think the first one was about fantasy, the second thing was about being independent, or being gay, and then the third thing was really about making hats. If you put all that in a liquidiser, I pop out the other end, you see?

AUTHOR: You’ve spoken before about the ribald camaraderie of the women in the millinery workroom–you must have always been very drawn to strong women?

stephen — Well, I think there was something about Shirley, who was the head of the workroom. If she’d been a miner, I would have followed her down the mine. She was an extraordinary teacher. I suppose somehow the yin and the yang of me and a strong woman always fit together quite well. I think I sort of see them as a leader, I can sort of fold myself around them and they can fold themselves around me. I mean, the complete idea that women are somehow less than men is so totally shocking, and so contrary to everything that I’ve ever experienced.

AUTHOR: Do you think the only hope now in society is the genuine global emancipation of women?

stephen — I don’t believe necessarily that we will move towards a feminine society very soon, but in order to have a more balanced view maybe we need to. A woman brings a different perception of things to the table, which is fantastic and to be celebrated, and they make very, very good politicians. Angela Merkel, she is an extraordinary politician, and whether you like her or you hate her, she’s somebody who the world takes seriously. I wish Michelle Obama would run for president, but I feel she is too sensible, sadly.

AUTHOR: What role do you think fashion, at its best, can play in affecting sociopolitical change?

stephen — I think the only time that fashion ever really makes sense is when it has sociopolitical comment. That’s when it really galvanises people. Whether it was Teddy Boys or Punk, or Rave, it always had that sociopolitical element to it. I saw this really fantastic quote from Winston Churchill during WW2. He was called upon to stop arts funding, the government had already really cut it back, but they wanted to stop it completely, and he said: “If we’re not fighting for culture and art, what are we fighting for?” I mean, fashion has got an incredibly important role to play in being a catalyst for change.

AUTHOR: Do you think with the incredibly fast turnaround of fashion, and its corporatisation, the glory days are behind us?

stephen — I think there are certain areas that are becoming so much more corporate, but there are some designers who are coming up who think all of that is as completely irrelevant as my generation did. I recently worked with the designer John Skelton, and he has that sort of insane passion and belief. He made his own set from old front doors that he had sourced from council houses, and then did a fashion show lit by oil lamps. It was fantastic and, you know, sort of bonkers and ridiculous and wonderful too, and so completely British. The clothes were exquisite and beautifully made, but at its heart, the subject he was dealing with was class and colonialism.

AUTHOR: It seems harder to find that authentic subcultural expression now. With so much noise, there’s no defined mainstream to kick against, just many streams happening at once...

stephen — Yes. I mean, 1976 was my first year at college and there was absolutely no option for me but to be a punk. It was a very galvanising thing because, you know, we certainly didn’t want to be anything that had gone before. Then in the early 80s, we were sort of in a vacuum left by punk and were just trying to find our own way again. It was so different then because if you wanted culture, you really had to work for it, which is why magazines like The Face and iD and Blitz and all of those were formed. What young people have now is social media, and these days, it’s very global as opposed to national. Obviously, my generation were in London doing the London thing and people like Jean-Paul Gaultier would come for the club scene, while conversely, we would look to New York as being like the exciting place to be, with CBGB and the Mudd Club. It was a genuinely social movement, whereas online is where the big social thing happens now. What’s strange, and this also goes hand-in-hand with the online thing, is that fashion then, once it had happened, was kind of dead or had finished, but now it has a life online and in exhibitions. It sort of continues. There are a whole new generation who are just discovering McQueen and Vivienne.

AUTHOR: You mentioned Gaultier. How key do you think unique Gaultier was in transforming the lexicon of fashion?

stephen — He made it his own, and he really ran very particularly with his sexuality, with the collection God Created Man instead of God Created Woman, like the Vadim film, and you know, he really did all that. In a funny way, though, I don’t think he could have done what he did without Vivienne. I think he took the world of Vivienne and the fact that she was questioning what clothes could be and then he developed his own thing. He’s an extraordinary designer, and I think it’s such a shame he’s not doing ready-to-wear because he was, and is, a complete visionary.

AUTHOR: What’s your notion of genius and how much do you feel is nature or nurture?

stephen — I’ve never been asked that before. I think it’s probably a combination of the two. To be a successful fashion designer, and this is in regard to somebody like John [Galliano], then, of course, there are things, maybe in your childhood, or whatever, which propel you to go and do that. Maybe it’s the dysfunction of your family, or your self perception, or awareness, and you try and work it out through clothes, or through art, or through your method of expression, and that’s incredibly important. I think you have to have a level of innate self-belief, as well. You have to have that ego–that sense you are right and, not that everybody else is wrong, but that it’s about you. To be a fashion designer is so difficult. It’s so competitive that unless you believe that, you will not succeed.

AUTHOR: Do you think you have to have a desire for attaining beauty? What is your personal definition of beauty?

stephen — What’s beauty? I think there’s beauty in simplicity of purpose – the one thing I would say about beauty is that it’s not studied. That’s why it is simplicity of purpose. In my own work, I think certain things I have made are beautiful, but I never intend to make them beautiful. Beauty is such a high target that it would be, in one way arrogant, and in another way, an impossible task to try and achieve. You can only see it in retrospect, you know? There are certain things, I might think are beautiful, or a beautiful idea, but then maybe they are not beautifully realised. I can only really see it afterwards upon reflection. I think somehow beauty is more a product of chance than design.

AUTHOR: How does that play into a notion of style?

stephen — I think style is related to beauty, but style is somehow a big breath of fresh air. When you observe style in somebody, it’s invigorating and it’s somehow a positive energy. When I think of the word style, though, I always think of The Clothes Show. I think the word style has to be the most 80s word on the planet.

AUTHOR: I tend to think of Leigh Bowery moments when I think of The Clothes Show...

stephen — Oh yeah, completely! I mean, Leigh is the perfect example here, because he would say himself ‘Oh, yes, I’m incredibly fashionable, and I’m very stylish!’. He’d be completely taking the piss out of himself and wouldn’t be taking it seriously, but then he would be somehow serious about it in working out his look. The poses that he stood in to have his photograph taken were ultimately poses which came out of 50s Vogue. He looks as though he came out of a Henry Clark or an Avedon.

AUTHOR: To mention style, when in regard to fashion, is to introduce a notion of added value?

stephen — The word style became very popular in the 80s because the word fashion was deemed to be ‘less than’ style. It was a bit like when, maybe 10 years ago, the word ‘luxury’ had to be brought in. Then, of course, fashion had to be associated with art when Raf was at Dior... It’s a funny thing, because as fashion is perceived as being something essentially frivolous, it needs to always have this added value of something ‘other’. So if you add style to fashion that means you’re somehow giving it a superior being; if you add luxury to fashion, then somehow it’s quantitative or made out of intrinsically precious materials; if you say that it’s artistic, it means that it’s more cerebral, and so on... Pure fashion is quite scary in that it is an art that is very difficult to understand and difficult to be part of. It’s not democratic, it’s not easy, it’s not friendly and it’s very expensive!

CREDITS:

BY JOHN-PAUL PRYOR

PICTURES BY STEPHEN JONES