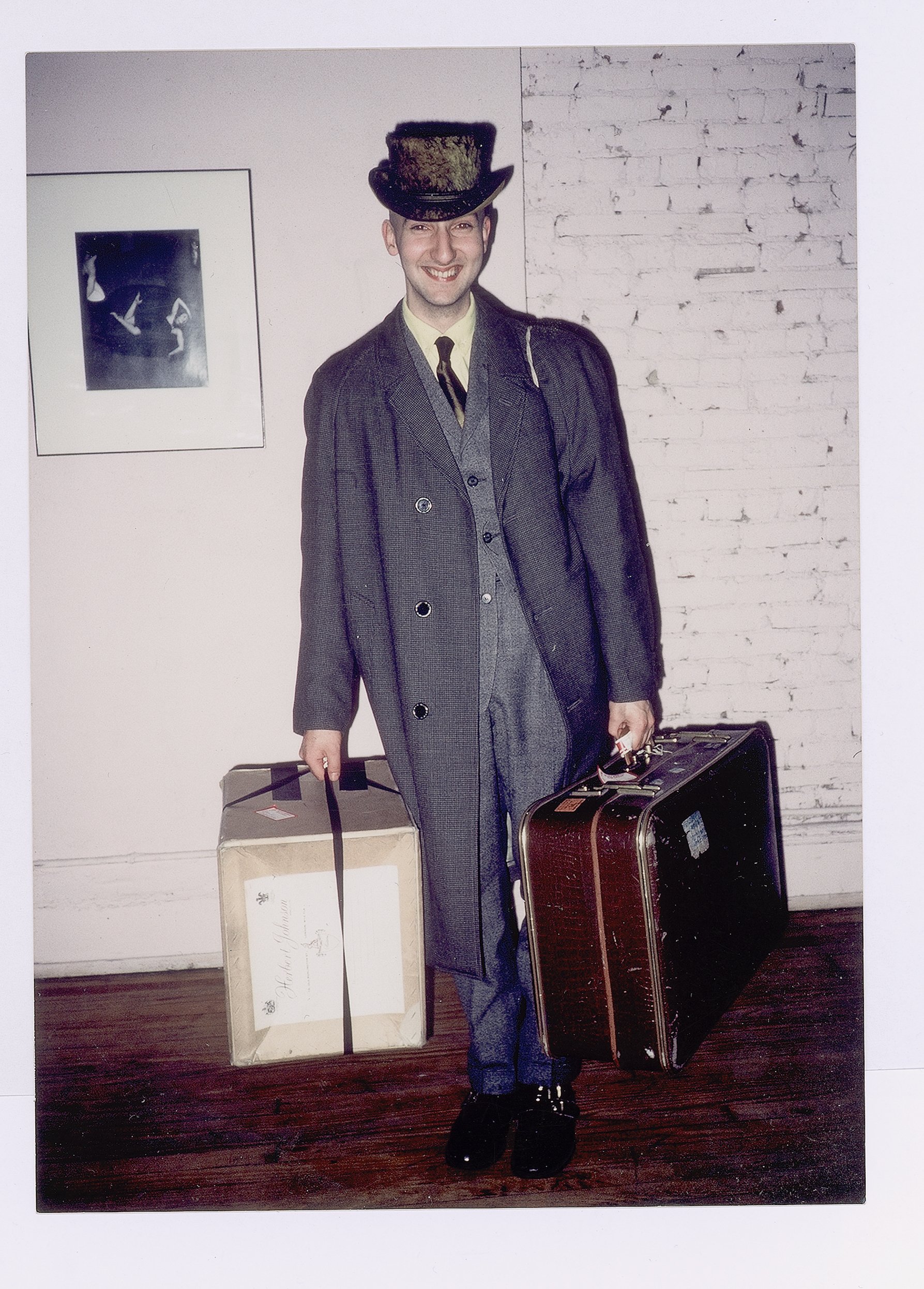

Art of Intention - Stephen Jones

“I think the only time that fashion ever really makes sense is when it has sociopolitical comment. That’s when it really galvanises people.”

– Stephen Jones

Sir Stephen Jones does not hold the accolade of being the most charming man in fashion for nothing. Ironic, erudite, and genuinely self-effacing, the Liverpool-born milliner with a cheeky glint in his eye has been an unparalleled force in the industry since the 80s, the decade he and his Blitz Kids peers came to define, one gender-bending fashion statement at a time. His vivacious energy and work ethic is nothing short of legendary and his talent ubiquitous. He’s provided uncompromising show-stopping visionary accompaniment to the likes of Galliano, Gaultier, and McQueen, to name check but a handful of the legends he has worked with, and to some of the celebrity sphere’s most groundbreaking artists, such as Grace Jones, Dita Von Teese and his lifelong friend, Boy George. Here, the man who has provided the perfectly balanced ‘cherry on top’ of some of the most iconic fashion moments of all time, tells AUTHOR why a thing of beauty can only be seen in retrospect, how the baton of anti-corporate subcultural identity is being carried forward by a new generation of outsiders, and why pure fashion is an art form so fearsome in its naked form that it can scare the living daylights of you.

AUTHOR: Can you remember any distinctive moments in childhood that set you out on your path in life?

stephen — There are a couple of things. When I was really young, five or six, or something, I used to watch puppet series’ on the TV – this was the era of Fireball XL5 and Thunderbirds – and I remember getting very confused because I felt that the shows were more real than the life that I inhabited with my parents. That was really the first thing. The other thing was that I knew I somehow didn’t fit in. I was at a very traditional boy’s boarding school in Liverpool and I remember buying some platform shoes, which I thought were fantastic and my housemaster saying, ‘Jones, for God’s sake! Take those high heels off!’. And I remember just thinking: ‘you are wrong! This is the way forward!’

AUTHOR: And it was this combination of feeling like an outsider and a penchant for fantasy took you to Saint Martins...

stephen — Well, the third thing was that I realised at Saint Martins that I couldn’t sew! So, I became a tailoring intern at a couture house, and next to the tailoring workroom was the millinery workroom, full of these wonderful older ladies. I transferred from one department to another and, after the first day, I knew this was what I wanted to do more than anything else. Those were three really defining moments. I think the first one was about fantasy, the second thing was about being independent, or being gay, and then the third thing was really about making hats. If you put all that in a liquidiser, I pop out the other end, you see?

AUTHOR: You’ve spoken before about the ribald camaraderie of the women in the millinery workroom–you must have always been very drawn to strong women?

stephen — Well, I think there was something about Shirley, who was the head of the workroom. If she’d been a miner, I would have followed her down the mine. She was an extraordinary teacher. I suppose somehow the yin and the yang of me and a strong woman always fit together quite well. I think I sort of see them as a leader, I can sort of fold myself around them and they can fold themselves around me. I mean, the complete idea that women are somehow less than men is so totally shocking, and so contrary to everything that I’ve ever experienced.

AUTHOR: Do you think the only hope now in society is the genuine global emancipation of women?

stephen — I don’t believe necessarily that we will move towards a feminine society very soon, but in order to have a more balanced view maybe we need to. A woman brings a different perception of things to the table, which is fantastic and to be celebrated, and they make very, very good politicians. Angela Merkel, she is an extraordinary politician, and whether you like her or you hate her, she’s somebody who the world takes seriously. I wish Michelle Obama would run for president, but I feel she is too sensible, sadly.

AUTHOR: What role do you think fashion, at its best, can play in affecting sociopolitical change?

stephen — I think the only time that fashion ever really makes sense is when it has sociopolitical comment. That’s when it really galvanises people. Whether it was Teddy Boys or Punk, or Rave, it always had that sociopolitical element to it. I saw this really fantastic quote from Winston Churchill during WW2. He was called upon to stop arts funding, the government had already really cut it back, but they wanted to stop it completely, and he said: “If we’re not fighting for culture and art, what are we fighting for?” I mean, fashion has got an incredibly important role to play in being a catalyst for change.

AUTHOR: Do you think with the incredibly fast turnaround of fashion, and its corporatisation, the glory days are behind us?

stephen — I think there are certain areas that are becoming so much more corporate, but there are some designers who are coming up who think all of that is as completely irrelevant as my generation did. I recently worked with the designer John Skelton, and he has that sort of insane passion and belief. He made his own set from old front doors that he had sourced from council houses, and then did a fashion show lit by oil lamps. It was fantastic and, you know, sort of bonkers and ridiculous and wonderful too, and so completely British. The clothes were exquisite and beautifully made, but at its heart, the subject he was dealing with was class and colonialism.

AUTHOR: It seems harder to find that authentic subcultural expression now. With so much noise, there’s no defined mainstream to kick against, just many streams happening at once...

stephen — Yes. I mean, 1976 was my first year at college and there was absolutely no option for me but to be a punk. It was a very galvanising thing because, you know, we certainly didn’t want to be anything that had gone before. Then in the early 80s, we were sort of in a vacuum left by punk and were just trying to find our own way again. It was so different then because if you wanted culture, you really had to work for it, which is why magazines like The Face and iD and Blitz and all of those were formed. What young people have now is social media, and these days, it’s very global as opposed to national. Obviously, my generation were in London doing the London thing and people like Jean-Paul Gaultier would come for the club scene, while conversely, we would look to New York as being like the exciting place to be, with CBGB and the Mudd Club. It was a genuinely social movement, whereas online is where the big social thing happens now. What’s strange, and this also goes hand-in-hand with the online thing, is that fashion then, once it had happened, was kind of dead or had finished, but now it has a life online and in exhibitions. It sort of continues. There are a whole new generation who are just discovering McQueen and Vivienne.

AUTHOR: You mentioned Gaultier. How key do you think unique Gaultier was in transforming the lexicon of fashion?

stephen — He made it his own, and he really ran very particularly with his sexuality, with the collection God Created Man instead of God Created Woman, like the Vadim film, and you know, he really did all that. In a funny way, though, I don’t think he could have done what he did without Vivienne. I think he took the world of Vivienne and the fact that she was questioning what clothes could be and then he developed his own thing. He’s an extraordinary designer, and I think it’s such a shame he’s not doing ready-to-wear because he was, and is, a complete visionary.

AUTHOR: What’s your notion of genius and how much do you feel is nature or nurture?

stephen — I’ve never been asked that before. I think it’s probably a combination of the two. To be a successful fashion designer, and this is in regard to somebody like John [Galliano], then, of course, there are things, maybe in your childhood, or whatever, which propel you to go and do that. Maybe it’s the dysfunction of your family, or your self perception, or awareness, and you try and work it out through clothes, or through art, or through your method of expression, and that’s incredibly important. I think you have to have a level of innate self-belief, as well. You have to have that ego–that sense you are right and, not that everybody else is wrong, but that it’s about you. To be a fashion designer is so difficult. It’s so competitive that unless you believe that, you will not succeed.

AUTHOR: Do you think you have to have a desire for attaining beauty? What is your personal definition of beauty?

stephen — What’s beauty? I think there’s beauty in simplicity of purpose – the one thing I would say about beauty is that it’s not studied. That’s why it is simplicity of purpose. In my own work, I think certain things I have made are beautiful, but I never intend to make them beautiful. Beauty is such a high target that it would be, in one way arrogant, and in another way, an impossible task to try and achieve. You can only see it in retrospect, you know? There are certain things, I might think are beautiful, or a beautiful idea, but then maybe they are not beautifully realised. I can only really see it afterwards upon reflection. I think somehow beauty is more a product of chance than design.

AUTHOR: How does that play into a notion of style?

stephen — I think style is related to beauty, but style is somehow a big breath of fresh air. When you observe style in somebody, it’s invigorating and it’s somehow a positive energy. When I think of the word style, though, I always think of The Clothes Show. I think the word style has to be the most 80s word on the planet.

AUTHOR: I tend to think of Leigh Bowery moments when I think of The Clothes Show...

stephen — Oh yeah, completely! I mean, Leigh is the perfect example here, because he would say himself ‘Oh, yes, I’m incredibly fashionable, and I’m very stylish!’. He’d be completely taking the piss out of himself and wouldn’t be taking it seriously, but then he would be somehow serious about it in working out his look. The poses that he stood in to have his photograph taken were ultimately poses which came out of 50s Vogue. He looks as though he came out of a Henry Clark or an Avedon.

AUTHOR: To mention style, when in regard to fashion, is to introduce a notion of added value?

stephen — The word style became very popular in the 80s because the word fashion was deemed to be ‘less than’ style. It was a bit like when, maybe 10 years ago, the word ‘luxury’ had to be brought in. Then, of course, fashion had to be associated with art when Raf was at Dior... It’s a funny thing, because as fashion is perceived as being something essentially frivolous, it needs to always have this added value of something ‘other’. So if you add style to fashion that means you’re somehow giving it a superior being; if you add luxury to fashion, then somehow it’s quantitative or made out of intrinsically precious materials; if you say that it’s artistic, it means that it’s more cerebral, and so on... Pure fashion is quite scary in that it is an art that is very difficult to understand and difficult to be part of. It’s not democratic, it’s not easy, it’s not friendly and it’s very expensive!

CREDITS:

BY JOHN-PAUL PRYOR

PICTURES BY STEPHEN JONES