Sotheby’s New Map

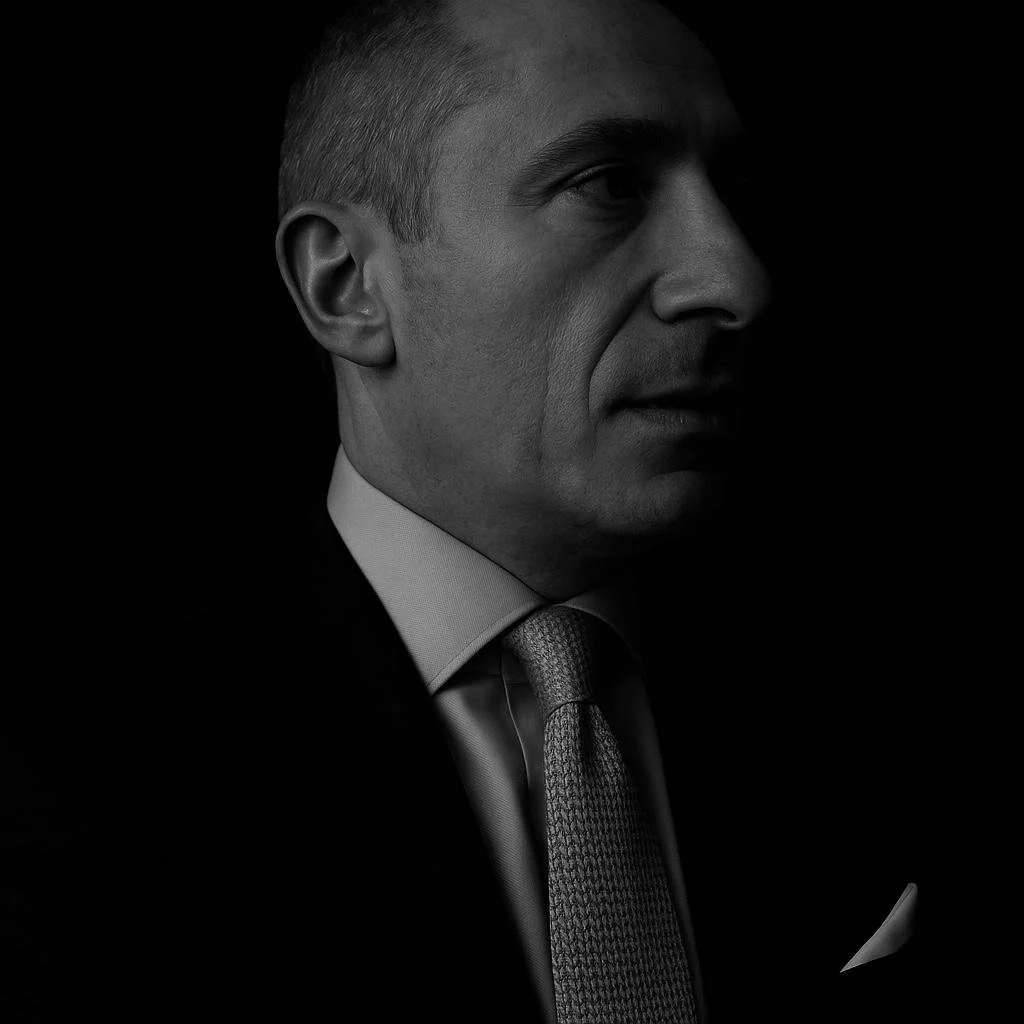

Katia Nounou Boueiz - Deputy Chairman, Middle East, Dubai

Abu Dhabi as a global nexus for auctions, private sales, and cultural diplomacy.

Maps don’t change loudly. They shift in boardrooms, in flight paths, in the quiet logistics of where masterpieces are sent and where capital flows back from.

This week in Abu Dhabi, that shift is visible.

For the first time, Sotheby’s is staging a full Collectors’ Week in the UAE capital: five live auctions on 5 December, a billion-dollar exhibition of art, jewellery, watches, handbags, collector cars and real estate, and a programme of talks and masterclasses that feels closer to a biennale than a sales week.

At the centre of this new map is Abu Dhabi — not as a satellite, but as a hub.

“We’re Dreaming Big”

Ford GT 2005-2006 Classic supercar

“So, what is your vision for Sotheby’s Middle East right now?” I ask Katia Nounou Boueiz, Deputy Chairman of Sotheby’s Middle East.

Her answer is immediate. “The vision is big,” she says.

“We feel like we’re in the middle of a cultural revolution in Abu Dhabi.

There are incredible strategic investments in museums and in luxury.

We’re privileged to be part of this revolution.”

Sotheby’s has formally incorporated in Abu Dhabi, backed by long-term investment and aligned with the Abu Dhabi Investment Office. Collectors’ Week is the first visible summit of that partnership.

“We’ve brought about a billion dollars of offerings,” Katia notes.

“Highly curated jewellery, watches, cars, fine art — the largest and most valuable exhibition an auction house has ever brought to the Middle East.

And this is the first auction by a leading international house in Abu Dhabi. It’s a huge milestone.”

Francis Bacon’s Three studies of Lucian Freud

Education as Diplomacy

If this were only about sales, the week would still be historic. But the strategy reaches further.

“I actually think we still have a lot to do in terms of education,” Katia says.

“That’s what Collectors’ Week is about. We’re bringing the works, yes, but also masterclasses, talks, fireside chats with leading experts in every category.”

Throughout 2–5 December, the St. Regis becomes a campus: jewellery literacy sessions, handbag connoisseurship, panels on Picasso, Jane Birkin, the future of collecting in the Gulf. Specialists are not just closing sales — they’re opening worlds.

“We want to build a collecting culture in Abu Dhabi,” Katia explains.

“We’ve come a long way — the museums here have done so much — but there’s still so much untapped potential.

For this to remain a rising global market, we need to keep growing the community.”

Education here functions as a kind of soft power: a bridge between global expertise and regional intuition, a way of aligning sovereignty with connoisseurship.

Ferrari Enzo

Abu Dhabi’s Advantage

For both Vanessa and Andrés, there’s one point they keep returning to: safety.

“We’re lucky to be in a place where people can wear jewellery, wear watches, drive cars, and feel safe,” Katia says.

“In today’s world, that’s becoming rare. So we thought: let’s show everything this region can host and enjoy.”

Morgane echoes this from the handbags side.

“In some cities, people hesitate to own very expensive pieces because they feel they can’t wear them,”she notes.

“Here, it’s different. People understand the craftsmanship — and they actually live with their luxury.”

This simple reality — that you can step out in a Kashmir sapphire, a Patek Star Caliber, a Himalaya Birkin, without fear — gives Abu Dhabi a unique role in the new map. It’s not just a place to store value, but to experience it.

Patek Philippe Geneve Watch

One Week, Five Auctions, A Long Horizon

On 5 December, five major auctions unfold back-to-back: Jane Birkin’s Le Voyageur as a single-lot sale; a $20 million single-owner jewellery and watches collection centred on The Desert Rose; an RM Sotheby’s car sale with McLaren race cars and hypercars; plus real estate and additional luxury offerings.

But the real horizon is longer. “Sky’s the limit,” Katia says simply.

“We want to introduce more auctions, more frequently.

Eventually, we want to bring full art auctions to Abu Dhabi — when the time and the market feel right. There is so much that is still untapped.”

She’s been coming to Abu Dhabi for 18 years.

“It’s incredible to see the evolution. I’m proud to be part of this story. And with our partners, we’re in such a good place to see this dream come true.”

Katia Nounou Boueiz - Deputy Chairman, Middle East, Dubai. Oona Chanel - Editor-in-cheif, Author Magazine

The New Map

In practical terms, Sotheby’s new map includes:

• Abu Dhabi as a permanent node for high-value auctions and private sales

• The Gulf as a natural home for multi-category, cross-disciplinary exhibitions

• A new generation of collectors — younger, more global, often female — moving freely between categories and price brackets

In symbolic terms, it marks a transfer of cultural gravity.

For decades, the map of “serious collecting” ran through New York, London, Geneva, Hong Kong. That map is being redrawn — not to erase those centres, but to acknowledge that another one has quietly lit up.

For now, it is marked by four days in December, a billion dollars’ worth of objects, and a series of conversations in a hotel on Saadiyat Island.

Over time, it will be marked by something harder to plot: the moment when the world stopped seeing Abu Dhabi as an offshore audience, and started seeing it as what it is becoming —

A place where the future of value is being decided.

Words by Oona Chanel for Author Magazine

Pictures courtesy Ron John

The Desert Rose: A Diamond’s Cultural Afterlife

Andres White Correal - Sotheby’s Chairman | Jewellery, EMEA

On how a 31.86-carat stone becomes a symbol, not just a commodity.

In the jewellery salon at St. Regis Saadiyat Island, the room doesn’t fall silent when you walk in. It tilts.

At the centre of that tilt is a single stone: a 31.86-carat Fancy Vivid Orangy Pink diamond known as The Desert Rose — the largest of its kind ever graded by the GIA, estimated at $5–7 million USD.

To call it “a diamond” feels almost insufficient. It is a colour field. A sunset. A thesis about rarity.

“It’s probably one of the most beautiful — and the biggest — GIA-certified orangey-pink stones in the world,”

says Andres White Correal, Chairman of Jewellery for Europe & the Middle East at Sotheby’s.

“A stone like this doesn’t sit in the market. It defines it.”

The Desert Rose - Vivid Orangy Pink diamond.

From Commodity to Cosmology

Technically, The Desert Rose is a pear-shaped diamond of exceptional saturation, a sunset-gradient of pink and orange so intense that even seasoned specialists struggle to describe it without resorting to metaphor.

But what makes it culturally potent is the way it sits in the room.

It is not shown alone in a vitrine, elevated beyond context. Instead, it is part of a single-owner constellation: Kashmir sapphires, Colombian Muzo emeralds, Boucheron rings, vintage Tiffany, and one of the rarest assemblages of pocket watches brought to market in decades — all from the same collector.

Patek Philippe luce watch. Patek Philippe 498G-010

“Everything you see here belongs to one consigner,”

Andrés explains.

“We wanted to bring the best of the best at every price bracket — from a €1,000 pearl pendant to this stone.

It’s incredibly rare to see someone collect in such a cohesive, intelligent way.”

The Desert Rose becomes, in that context, not just a hero lot but a keystone: the gravitational centre of a life’s eye.

Cartier-Golden Canary Diamond Necklace

Patek Philippe Star Caliber 2000

Charged Objects

What Andrés says next is where the stone moves beyond appraisal and into afterlife.

“I believe stones get charged with things.

When you hold a jewel, it becomes warm with your warmth and your energy.”

This is where The Desert Rose leaves the narrow world of luxury reporting and steps into something else: it becomes a vessel for human memory.

A future wearer — unknown yet already imagined — will bring their own story, their own pulse, their own warmth to it. The stone will leave Abu Dhabi different than it arrived: re-coded by another set of hands.

In a region where collectors are increasingly drawn not only to value but to meaning, that idea lands with particular force.

“Abu Dhabi has one of the most selective audiences in the world,”

Andrés notes.

“They understand what’s best and what’s unique. You want to bring them objects that are worthy of that attention.”

Ruby and Diamond Necklace

The Desert Rose as Metaphor

The Desert Rose is being auctioned in a city that has built its own cultural landscape almost from sand: Louvre Abu Dhabi, new museums, sovereign collections, a blossoming of galleries and foundations. In that sense, the stone’s name feels almost prophetic.

It is a mineral fact — 31.86 carats, Fancy Vivid Orangy Pink — and at the same time a metaphor for what’s unfolding here: something rare, saturated, and quietly world-redefining.

One day, this diamond will leave the vitrines of Collectors’ Week and disappear into a private life. It will sit on a hand, attend dinners, cross borders, outlive its owner.

But its afterlife will always circle back to this moment in Abu Dhabi — to the week when a desert city and a desert-named stone met and recognised each other as peers.

RM Sotheby’s Abu Dhabi

At 8 pm GST, a fleet of 32 exceptional automobiles—including a visionary “Triple Crown” of future McLaren race cars—brings the language of collecting into the realm of speed and engineering.

Ruby and Diamond Ring

Beyond the auctions, over $100 million in diamonds, colored stones, high jewelry, handbags, and watches is being offered for private sale: from the largest flawless diamond in the world to a deep green diamond of staggering rarity, and covetable Birkin and Kelly bags displayed like small, controlled miracles.

Words by Oona Chanel for Author Magazine

Pictures courtesy Ron John

The Week the Middle East Became the World’s Gallery

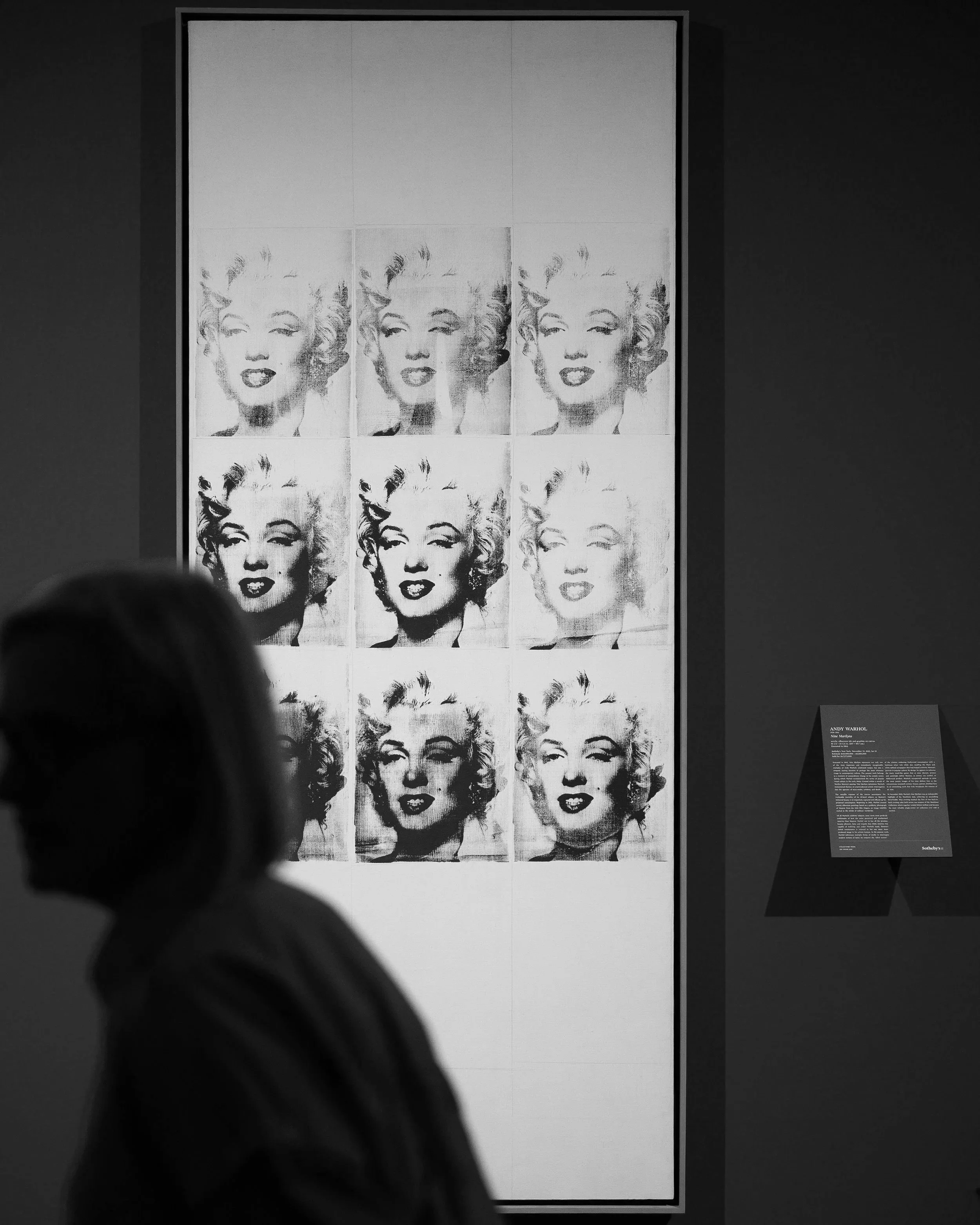

Nine Marilyns by Andy Warhol

Sotheby’s Collectors’ Week Abu Dhabi

From 2–5 December 2025, a new cultural axis is quietly locking into place in the gilded interiors of the St. Regis Saadiyat Island. Sotheby’s—longhand for provenance, prestige, and the theatre of the auction room—has brought over $1 billion USD of art, jewelry, handbags, watches, cars, and even architecture to Abu Dhabi.

It is not simply a showcase.

It is a declaration of where the world now turns its gaze.

“Abu Dhabi isn’t just hosting masterpieces. It’s defining the conditions in which they are seen.” — Oona Chanel

Abu Dhabi as Atmosphere, Not Just Location

Collectors’ Week is born of a particular alignment:

Sotheby’s, the Abu Dhabi Investment Office (ADIO), and the long-range vision of His Highness Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan bin Khalifa Al Nahyan, whose cultural patronage has helped turn the city into a gravitational field for art and luxury.

Unlike the compressed density of London or New York, Abu Dhabi gives the works air. In one suite, Rembrandt’s Young Lion Resting—on loan from the Leiden Collection ahead of its February 2026 sale—anchors the room with Old Master gravity. Across the space, Banksy’s self-shredded Girl Without Balloon hums with postmodern defiance, the now-legendary moment of self-destruction recast as a relic rather than a meme.

Nearby, Gustav Klimt’s Dame mit Fächer (Lady with a Fan)—believed to be his final portrait—glows with late-period sensuality; Piet Mondrian’s Composition No. II compresses modernity into lines and primary fields; and the Guennol Lioness, a three-inch Mesopotamian sculpture that still holds the auction record for an antiquity, sits in its own small field of reverence.

Abu Dhabi doesn’t flatten these works into spectacle. It lets them speak to one another.

Bansky, Girl With Ballon.

A Constellation, Not a Collection

At the heart of the week lies a series of live auctions on 5 December—five consecutive sales that together form the most valuable auction series ever staged in the Middle East, with around $150 million in luxury offerings.

The Brikin Voyageur, owned by Jane Brikin between 2003 and 2007

Among them: Le Voyageur: Jane Birkin’s Handbag

A single-lot evening sale at 5:45 pm GST.

The black Hermès Birkin Le Voyageur—one of only four made for Jane Birkin after the sale of her original prototype—is covered in silver-ink inscriptions in her own hand, including “Mon Birkin bag qui m’a accompagné dans le monde entier.” Estimated at $240,000–440,000, it sits at the intersection of fashion history and intimate relic.

Rolex Sky-Dweller

Precision and Brilliance: Prestigious Jewels & Watches from an Important Private Collection

At 6 pm GST, one of the most significant single-owner collections in decades comes under the hammer: rare diamonds, Kashmir sapphires, Colombian emeralds, signed Art Deco masterpieces, and the watch market’s own unicorns.

1991 Mclaren MP4/6

RM Sotheby’s Abu Dhabi

At 8 pm GST, a fleet of 32 exceptional automobiles—including a visionary “Triple Crown” of future McLaren race cars—brings the language of collecting into the realm of speed and engineering.

Beyond the auctions, over $100 million in diamonds, colored stones, high jewelry, handbags, and watches is being offered for private sale: from the largest flawless diamond in the world to a deep green diamond of staggering rarity, and covetable Birkin and Kelly bags displayed like small, controlled miracles.

The Desert Rose - Vivid Orangy Pink diamond.

The Desert Rose: When a Stone Becomes a Story

At the centre of the jewelry room, beneath controlled, almost ceremonial lighting, lies The Desert Rose: a 31.86-carat Fancy Vivid Orangy Pink diamond, the largest of its kind ever certified by the GIA.

“A stone like this doesn’t sit in the market. It defines it.”

— Andres White Correal, Chairman of Jewellery, Europe & Middle East, Sotheby’s

White Correal explains that The Desert Rose and the surrounding jewels and watches all come from a single international collector—a rarity in itself.

“We wanted to bring the best of the best in every bracket,” he says. “You have The Desert Rose at an estimated $5–7 million, but you also have a €1,000 pearl pendant. A textbook Kashmir sapphire, a Muzo emerald, a Boucheron ring, a Harry Winston ruby set. It’s a full spectrum. We wanted everyone who walks in to find something they could imagine taking home.”

His vision for the region is anything but tentative.

“The level here is already wonderful. The attention, the curiosity—it tells us these pieces are understood. And in the UAE, people don’t just lock things away; they live with them. That energy is something we miss in many parts of the world.”

Asked what he would keep for himself, he doesn’t choose the headline diamond.

“I’m more of a jewel person than a stone person,” he smiles. “The Kashmir sapphire or the Colombian emerald—they’re smaller, but they have this old magic. Stones hold warmth. They remember the people who wore them.”

Hermès Birkin Himalaya Bag.

Legacy Wrapped in Leather

If the Desert Rose is the jewel that defines the week, the emotional spine of Collectors’ Week is, improbably, a black leather bag.

Morgane Halimi

Global Head of Handbags & Fashion, Sotheby’s

“When I joined in 2021, there wasn’t a fully formed handbags department,” says Morgane Halimi. “Today, we’re a global division—New York, Hong Kong, Paris, London—and now Abu Dhabi.”

Under her leadership, Sotheby’s has turned handbags from a niche into a serious collecting category, with sales growing by around 60% in four years and a demographic unlike any other: largely women, most under 45, many in their 20s and 30s.

“Our clients are emotionally literate,” Halimi notes. “They don’t just want the logo. They want longevity, craftsmanship, a story. They want to carry their investments, not just vault them.”

Last summer in Paris, she presided over the record-breaking sale of Jane Birkin’s original Hermès Birkin, which achieved over $10 million and instantly became a modern myth. That very bag is now in Abu Dhabi as part of the Icons exhibition—no longer just an accessory, but a case study in how an object can move from functional to legendary.

This week, the focus shifts to Le Voyageur, the bag Birkin carried from 2003–2007, its interior lined with her notes in silver ink.

“It’s not just personal,” Halimi says. “It’s a fingerprint. A soulprint. You feel her presence in the wear, the doodles, the phrases. You’re not just buying a bag—you’re entering a life.”

Handbags, in her view, have finally joined the upper ranks of collectible culture.

“They’re heirlooms now,” she adds. “Objects of heritage. And Abu Dhabi understands that instinctively.”

Zwei Kerzen (Two candles) by Gerhard Richter.

The Middle East as Vision, Not Footnote

If Halimi and White Correal map the vertical depth of collecting—stone and leather, jewel and legacy—Vanessa Marcil-Hoffmann, Head of Sotheby’s Middle East, maps the horizontal horizon.

Vanessa Marcil-Hoffmann

Head of Sotheby’s Middle East

“We’re in the middle of a cultural revolution in Abu Dhabi,” Marcil-Hoffmann says. “Museums, foundations, long-term development plans—it’s an ecosystem. We don’t see this as a one-off moment; we see it as a chapter in a much larger story.”

Collectors’ Week, she explains, is as much about education and community as it is about sales. Throughout the week, Sotheby’s is hosting over a dozen talks, panels, and daily masterclasses: conversations with Christian and Yasmin Hemmerle, Diana Picasso, Marisa Meltzer, sessions on gemstone grading, watch movements, handbag provenance, and the alchemy of building a collection.

These sit alongside behind-the-scenes handling sessions, where visitors learn not only how to look—but how to think like collectors.

“We’ve come a long way,” she says. “The level of knowledge, desire, and hunger in the region is extraordinary. But building a sustainable collecting culture means continuing to share expertise, open dialogues, and invite people into the process—not just the results.”

Her favourite works in the exhibition? She doesn’t hesitate.

“For art, the Klimt. It feels like it holds his last breath. For jewelry, The Desert Rose. It’s like wearing a sunset. No woman would say no to that.”

Looking ahead, her vision is expansive but measured.

“The sky is the limit, but we move one rooted step at a time. More auctions. Eventually, art auctions in Abu Dhabi when the timing is right. More collaborations with local institutions. We’re not here as visitors. We’re here as partners.”

Gradiva by Salvador Dali. Guennol Lioness

A New Cartography of Taste

Behind the glamour, there is also infrastructure. In October 2024, Abu Dhabi’s investment and holding company ADQ took a minority stake in Sotheby’s—the largest investment in the global art industry since the auction house’s 2019 acquisition by Patrick Drahi. Sotheby’s has now formally incorporated in Abu Dhabi, adding a regional presence to its global network.

Collectors’ Week follows on the heels of an April presentation of over $100 million in rare colored gems in Abu Dhabi and a historic October fine art show at the Bassam Freiha Art Foundation, featuring van Gogh, Gauguin, Frida Kahlo, Munch, Magritte, and Pissarro.

In other words: this week is not a beginning. It’s an escalation.

“Abu Dhabi represents a powerful convergence of visionary ambitions, limitless opportunities, and cultural vibrancy,” notes Jean-Luc Berrebi, a Sotheby’s board member focused on the UAE. “The region is redefining global demand for art and luxury.”

Piet Mondrian, Composition No II.

Exhibition Highlights

Rather than a trophy list, the highlights read like chapters in a larger narrative: The Desert Rose—a 31.86-carat Fancy Vivid Orangy Pink diamond, the largest of its kind, glowing like a sunset held in the hand; Jane Birkin’s original Hermès Birkin—sold for over $10 million in Paris; the Le Voyageur Birkin—covered in her handwritten notes; Gustav Klimt’s Dame mit Fächer; Banksy’s Girl Without Balloon (self-shredded); Rembrandt’s Young Lion Resting; the Guennol Lioness; the Patek Philippe Star Caliber 2000; and McLaren’s “Triple Crown Project” cars.

Taken together, they form not just a cross-section of value—but a map of what humanity chooses to remember.

Rembrandt Harmensz young Lion Resting.

The Collector, Rewritten

What emerges most clearly from this week is not the scale of wealth, but the shape of the new collector: young, often female; cross-disciplinary—moving fluidly between watches, wine, handbags, cars, diamonds, and fine art; less interested in secrecy, more interested in story; comfortable with the idea that a handbag can sit beside a Rembrandt drawing in the same room, and the dialogue makes sense.

The Middle East, and the UAE in particular, embodies this evolution. It is no longer a “new market” to be educated. It is a producer of taste, a co-author of provenance, and increasingly, a place where the most important pieces in the world come not just to be sold—but to be seen.

“This week is not about one sale,” as one advisor quietly shared with Author Magazine. “It’s about who gets to decide what matters.

Words by Oona Chanel for Author Magazine

Pictures by Ron John

AI WEIWEI - The Radical Influence Of Drella

THE INFAMOUS PROVOCATEUR ON THE ENDURING INFLUENCE OF ANDY WARHOL

“If you study The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, then every sentence is like a Twitter sentence. It’s very

interesting, light communication; not old democratic, but new democratic”

– Ai Weiwei

To say that the iconoclastic cultural firebrand Ai Weiwei needs no introduction would be trite. He is one of the most outspoken and provocative artists of the modern era, creating highly politicized work defined by its social conscience and explicit two-fingered salutes to the draconian machinations of the

establishment. In this exclusive extract from AUTHOR, he tells us of his profound appreciation for the work of a very different icon from another era, Andy Warhol, whom he considers the key protagonist of a paradigm shift in art, published with previously unseen images from his close friend and confidante, Larry Warsh, one of his most significant collectors.

“Warhol made commercial art as art, and this was a political statement because, at that time, no one believed commercial art could be art–they were all looking for high art. But Warhol put ordinary people’s values into his work, and he succeeded. He placed an advert in The New York Times that said, ‘Whoever pays, I will give them a portrait.’ This was a very, very important statement–that the work belongs to average people, whoever meets the price. That’s a very democratic moment.

Today, we have the advantage of the Internet. I think Warhol would have dreamed to have the Internet. If you study Andy Warhol’s philosophy from A to Z and back again, then every sentence is like a Twitter sentence. It’s very interesting, light communication; not old democratic, but new democratic.

That’s very important. The internet is like a Woodstock moment, but in information – movies, documentary films, events; it rolls out information twenty-four-seven...

Nobody can stop that kind of creativity. It’s not about a product, but it’s about communication; how we can reach out and achieve something we can never even imagine.

Interview by JOHN-PAUL PRYOR

Special thanks to LARRY WARSH

Pictures courtesy of Ai WeiWei

FIN DAC - Art, Identity, and the Collective Consciousness

Photography: Rankin

In this edition of Author Magazine, we delve into a rare and intimate conversation with Fin Dac, the visionary street artist renowned for his striking murals that blend bold iconography with quiet introspection. His art doesn’t merely celebrate cultural icons; it reinvents them, using the public sphere as a canvas to explore themes of identity, agency, and legacy. In the interview, “Art, Identity, and the Collective Consciousness,” Fin Dac opens up about his creative philosophy, revealing a process that’s as much about connecting with a collective human experience as it is about personal expression.

As he reflects on his influences—Warhol’s audacity, Basquiat’s raw energy, Kahlo’s unflinching self-awareness—Fin Dac speaks to the complexity of making art that feels both timeless and fiercely relevant. This dialogue with Founder and Editor In Chief of Author Magazine Oona Chanel offers a unique window into his world, capturing the alchemy of aesthetic precision and philosophical inquiry that makes his work resonate on a global scale. For Fin Dac, each piece is more than a mural; it’s a conversation with the past, a meditation on the present, and a bold imagining of the future. This feature invites readers to experience his journey not just as an artist but as a thinker, whose art continually reflects and reshapes our shared cultural consciousness.

OONA: “Your work fuses contemporary art with cultural icons like Warhol, Basquiat, and Frida Kahlo. Beyond homage, how do you reimagine their legacies to speak to today’s cultural, social, or political concerns? Is there aspect to how you engage with these icons? In reinterpreting their legacies, do you feel you're tapping into a shared cultural consciousness that transcends time? What nuances of their work or personal histories resonate with you in a deeper, perhaps more spiritual way?”

FIN: “As I discuss in my upcomingshow book, this project gave me a unique opportunity to pause and truly reflect on my approach to making art—a first in my career. Immersing myself in the design choices, colour palettes, and techniques of these artists not only deepened my understanding of their work but also led me to a more profound awareness of my own style. I aimed to find a convergence point where their aesthetics could meet and blend seamlessly with mine. Initially, I gravitated towards my childhood favourites, driven by a personal connection. However, as the project evolved, I broadened my focus to include artists who held historical significance, shared similar perspectives, or had undergone parallel artistic journeys. Some were even chosen for the complexity of their relationships with their muses—historically fraught dynamics that I consciously positioned myself in contrast toin my own art career. In embracing these elements, I aimed to enter the mindset of these iconic artists, channelling their spirit and intentions while infusing them with a contemporary context. This allowed me to engage with their legacies in a way that feels both authentic and resonant with today’s cultural dialogue.

OONA: “If your art existed in a dimension where no one could perceive it, would it still hold meaning? When the act of observation is stripped away, does art retain its inherent value, or is its significance dependent on an audience? How does contemplating this void impact your understanding of creation and validation—both from others and from within yourself?”

FIN: “I believe there’s a distinction between the artist’s meaning and the audience’s meaning. For me, the act of creation carries intrinsic value because of what I experience in the process; I think that’s true for many artists. My commitment to this approach stems from the fact that external validation was never my driving force. That said, as an artist, you do need an audience to support your work for it to survive, thrive, and evolve. This dynamic can blur the lines between creating for oneself and for others. I imagine the lack of recognition was a source of deep frustration for someone like Van Gogh during his lifetime, yet history has proven his work was never without worth—just not valued in its own time. In my early career, financial reward wasn’t a consideration. I wasn’t creating for the sake of gain but because, for the first time, I felt completely aligned with what I was meant to put into the world. I trusted, perhaps naively, that if I remained authentic to that vision, I would ultimately receive what I needed or deserved in return.”

OONA: “Your portrayals of women, with their blend of beauty and strength, challenge traditional representations. What techniquesor cultural references do you find essential to reshaping the narrative of female representation in art? Is there an elements to your depictions of women, something that transcends the socio-political and taps into universal truths about identity, strength, and femininity? How does this contribute to your broader dialogue on representation?”

FIN: “From the very beginning, my intention was to neither objectify or sexualize the women in my work. To achieve this, I made a conscious decision to move away from the traditional, often power-imbalanced dynamic between artist and muse. Instead, I focused on granting my models complete agency in shaping how they were represented. I avoided traditional photoshoots or directed sittings, and instead, allowed them full controlover the selection of photos and poses they were comfortable providing for the work. This approach created an environment where the models were never left questioning my intentions or feeling unsure about the scenario. I believe this level of respect translates into the art itself—when the subjects are grounded in their own sense of power and autonomy, it becomes easier for me to reflect that strength and authenticity in the final piece. In this way, my portrayals aim to transcend the socio-political, reaching into something more universal about identity and femininity. By consciously respecting their agency, I seek to foster a narrative where beauty and strength coexist naturally, encouraging a broader dialogue on what it means to genuinely represent women without imposing external narratives onto their stories.”

OONA: “Your work with the Frida Kahlo Foundation is a honour. Were there moments in the creative process where you felt Kahlo’s presence, as if she were guiding your interpretation? How did you balance the responsibility of paying tribute to her image with your own creative instincs?”

FIN: “The creative process for this particular mural presented its own set of challenges, largely due to navigating the rights held by photographers who have a say in how Kahlo’s image is depicted, especially if it involves specific clothing or elements captured exclusively in their photos. The negotiations took an inordinate amount of time but it was crucial to respect the wishes of all creators involved. Despite these limitations, the essence of Kahlo—her strength, resilience, beauty, and distinctive style—made it clear that I would find a way to honour her legacy. She embodies everything I aim to convey in my work, so even within the constraints, there was an unshakeable sense of purpose guiding me. I approached the mural with deep reverence, balancing the weight of her legacy with my creative instincts to do justice to her image in a way that felt both authentic and powerful.”

OONA: ”Your murals frequently engage with cultural identities, such as Eurasian women in traditional dress. How do you navigate the fine line between cultural authenticity and artistic freedom in your representations? How do you ensure that your work honours the cultures you depict while also pushing artistic boundaries? Have you faced criticism for your approach, and how do you respond to feedback, particularly from the communities your work engages with?”

FIN: “My work aims to appreciate and celebrate these cultures, focusing on the women and the traditional attire that is gradually being overshadowed by modern trends. However, I strive to create a distinction from the conventional portrayals of women from these regions. There are key differences in the stance, posture, and gaze in my pieces—subtle elements that shift the power dynamic to the subject being viewed, rather than the viewer. I find myself drawn to places like Japan, where creativity is infused with a pursuit of absolute perfection, not just aesthetically but in every detail. This pursuit of precisionand dedication resonates with my own approach to art, where I strive for a similar level of rigor and integrity.My work blends Eastern and Western influences, much like some of my favourite artists—Aubrey Beardsley, Patrick Nagel, and Toulouse Lautrec. I don’t focus strictly on authenticity, but rather on respecting the culture while introducing my own alternative style and perspective. The painted mask motif, in particular, ensures that each piece is unmistakably my interpretation, rather than a direct representation.While I may have faced questions or critiques about my approach, I’ve always been open to listening and learning from the communities I engage with. My goal is to honour their stories, and if my work sparks a conversation or deeper reflection, then I see that as an opportunity to refine and grow as an artist.”

OONA: “As street art becomes a high-value commodity, how do you reconcile its raw, unfiltered origins with its current market status? Do you believe the commercialization of street art alters its purpose or impact.? As street art becomes a high-value commodity, how do you reconcile its raw, unfiltered origins with its current market status? Do you believe the commercialization of street art alters its purpose or impact?”

FIN: “Street art as a whole isn’t a high-value commodity—it’s only a select few artists who have reached that level of collectability. Similarly, the broader impact or purpose that’s often associated with street art can really only be attributed to a handful of names. For most artists, it’s about doing what they love and finding a way to keep going. Personally, I’ve stayed true to my original intentions: simply to put my work into the world to be seen. Over time, my studio work and street work have naturally diverged from each other, allowing me to approach them with distinct mindsets. When I’m creating in public spaces, my aimis to connect with the community and the surroundings in a meaningful way. In the studio, however, I’m painting purely for myself, driven by my own creative instincts. By maintaining this separation, I can keep the raw spirit of street art alive, regardless of its evolving status in the market.”

OONA: “Your engagement with social causes through art often feels more like a statement than charity. How do you choose the causes you support, and how do you see your work making a tangible impact? Is there a particular project or cause that felt especially transformative for you, where you could see your art effecting real change? How does this impact shape your artistic decisions moving forward?”

FIN: “I gravitate towards projects where I can have a direct, meaningful involvement and a genuine connection to the cause. For me, these projects sit at the intersection of ‘art therapy’—where the act of creating brings healing to the artist—and ‘art as therapy,’ where the artwork itself provides solace or inspiration to those who engage with it. This dual perspective allows me to approach each project with both authenticity and purpose. One particularly impactful project took place in Cambodia, where my collaboration with the Terry McIlkenny Trust helped raise funds to establish scholarships for students at The Phrase School of Performing Arts. Seeing the direct results of that effort and witnessing how it enabled young artists to pursue their passion was deeply fulfilling. However, the most transformative project to date was with The Nightingale Project in London where I painted a mural in the private garden of a women’s mental health facility. The impact wasn’t quantified in monetary terms, but rather in the expressions of theinpatientsthere. I invited andencouraged them to add their own colourful touches to the mural, turning it into a living metaphor for how they could colour their lives when they believed in themselves. Witnessing that transformation was incredibly powerful. These experiences continually reinforce my commitment to projects where the work has a tangible, human impact. Moving forward, I’m inspired to keep seeking out opportunities where art can act as a bridge to healing, growth, and transformation.”

OONA: “You’ve already explored themes of cultural identity, gender, and legacy in your art. Are there new, uncharted territories that are calling to you? What subjects or themes are beginning to pull you in different directions? How do these align with the trajectory of your work thus far, and what excites you about exploring them in the future?”

FIN: “Working on my new exhibition has revealed angles I hadn’t even considered before. In paying homage to the artists who’ve inspired me, I ended up learning just as much about myself and my own approach as I did about theirs. I’ve begun incorporating some of these insights into my new work, exploring an intersection between my usual style and two of my greatest artistic influences: graphic novels/manga and Japanese woodblock prints. This blend has the potential to bring an added element of playfulness to the process, and possibly the final artworks as well. As for trajectory, it’s not something I consciously focus on. My career has always unfolded organically, without forcing it in any specific direction. I trust that whatever force is guiding me will continue to do so, and I’m content to follow it wherever it leads, as long as it feels instinctively right. That sense of fluidity and openness is what excites me most about the future and where it might take my work.”

OONA: “Do you see yourself as the originator of your work, or merely a conduit for something larger? Many artists describe themselves as vessels for creative forces that flow through them rather than from them. Do you believe you channel a greater consciousness in your work, and if so, how does this belief shape your creative process? Is there a metaphysical connection between the artist and the art that transcends personal authorship?”

FIN: “I definitely see myself as a conduit. I’ve always felt that I’m not fully in control of what I create, especially given that I have no formal artistic training. When I’m painting, it might seem like I’m deeply focused, but in reality, I’m often in a sort of autopilot state, completely zoned out. Hours can pass without me fully realizing it, almost as if I’m not entirely present in my body. Even in the design phase, while I do prepare initial concepts on my laptop or iPad, the final painting rarely follows the digital blueprint exactly. Colours, patterns, and certain elements seem to come together organically on the canvas, often shifting away from the original plan in ways I didn’t consciously decide. I’ve learned to trust this process and simply allow it to happen. There’s something liberating about surrendering to that creative flow, and it shapes my work in ways that feel instinctive and authentic, beyond my own intentions or preconceptions.”

OONA: “If you removed yourself from the narrative of your art—stripping away your identity, your name, even your signature—would the act of creation still fulfil you? How would this self-imposed anonymity alter your metaphysical relationship with your work? Would your art take on a more universal quality, or do you believe your presence, however unseen, remains integral to the art itself?”

FIN: “For a significant part of my street art career, my name wasn’t attached to my murals at all. In the beginning, I signed my work with a dragon logo instead of a name, and when I eventually stopped using that logo, I still didn’t feel the need to add my name. I believed that the distinctive colour mask around my female subjects’ eyes would serve as a recognizable marker of my work or brand. It wasn’t until around 2018 that I started signing my name on my work after creating a new logo. In my opinion the absence of a signature or name allows the art to stand on its own, creating a more open connection between the viewer and the work, unfiltered by the influence of my identity. For me, the fulfilment comes from the act of creating and the connection it forms with the audience, regardless of whether my name is there or not. While my presence is embedded in the work through the themes, style, and recurring elements, I believe stripping away my identity wouldn’t diminish that connection—it might even enhance it by inviting viewersto engage more deeply with the art itself.”

Images by Westcontempeditions

Interview by Oona Chanel

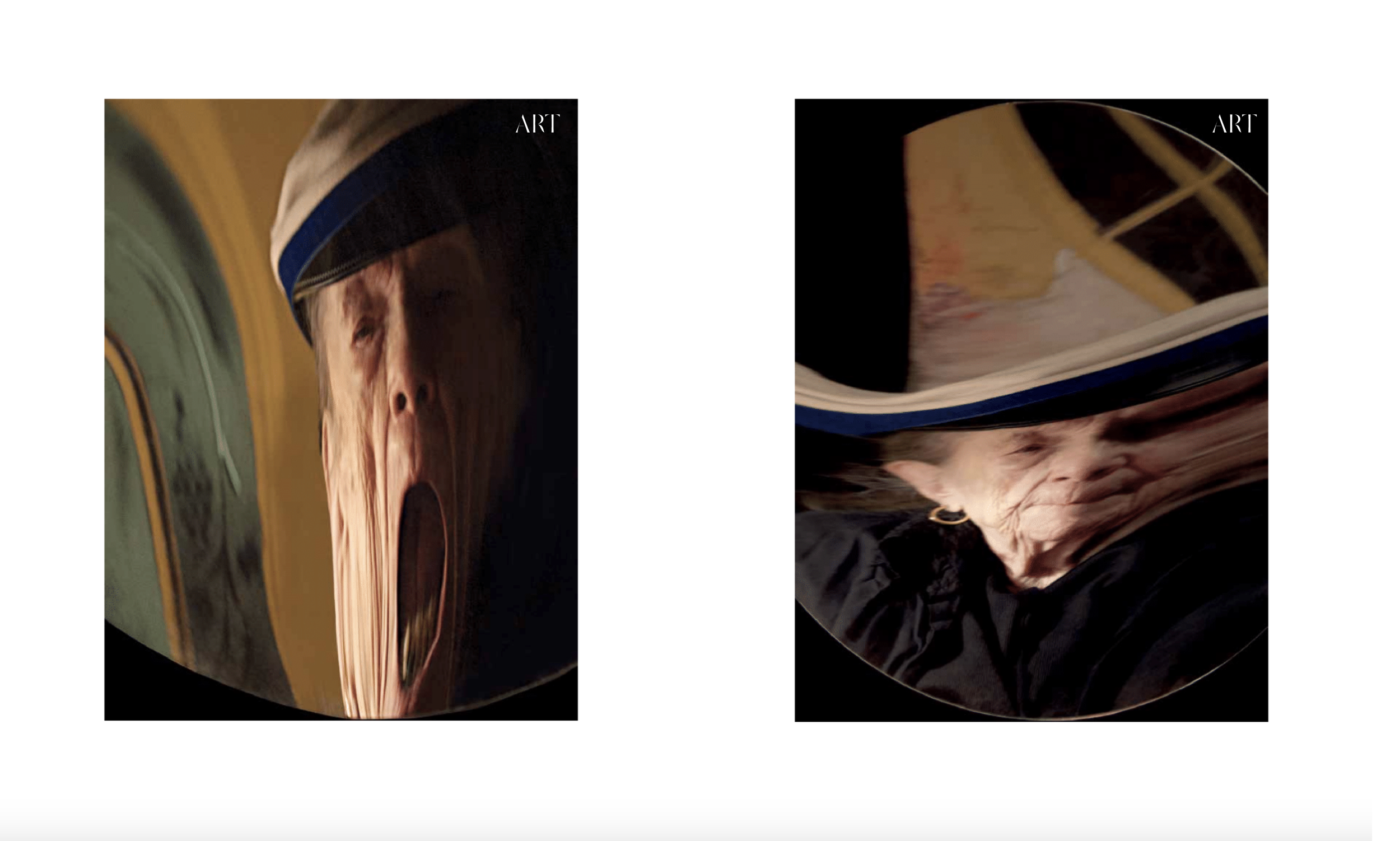

The last year dying with Louise Bourgeois by Alex Van Gelder

ALEX: “I first met Louise Bourgeois in the '80s at Le Select, the Parisian bar frequented by American writers. She was waiting for her governess, Susie Cooper, and I had just flown in from Africa. We started talking, and I took both ladies to my house at Les Gobelins to show them the African art I had brought back. I have a long-lived passion for African art and had started exporting it to collectors in Europe. Louise was impressed. Before leaving for New York, Louise offered me the opportunity to follow her, as my introduction to the underground movement. I decided to first go back to Africa, but we did continue to meet on a regular basis. Encouraged, I started working seriously as a photographer around the start of the new millennium.”

ALEX: “At one of our debriefs, I showed Louise some of my work on graveyards. She said, "Wonderful." We decided to work together, and she became my muse. I went to New York, and we worked together with intensity for a whole year. We bonded over terminal illnesses, and we knew this would be our last work to be seen. I was diagnosed with the same illness that Louise's mother had passed away from; hence, she was reliving her final days through my own. It was an intense time, as we were both very ill and knew we had limited time to leave something meaningful behind. The following series has been chosen for Author from that year when we worked together so closely. She died in 2010, and I survived, miraculously. However, the images of Louise will live forever, and I think we truly did capture something unique together.”

— Alex Van Gelder

Images by Alex van Gelder

Interview by Oona Chanel

Unveiling the Visionary: Gian Paolo Barbieri and the Art of Photography

In the realm of fashion photography, few names evoke as much admiration and respect as Gian Paolo Barbieri. Renowned for his meticulous attention to detail and a profound ability to capture the essence of his subjects, Barbieri has created a legacy that transcends time. In this exclusive feature, we are privileged to present ten never-before-seen images, showcasing not only the iconic Monica Bellucci but also other celebrated figures of their era. Each photograph is a testament to Barbieri's unmatched talent in blending beauty, art, and storytelling into a single, unforgettable frame.

But who is the man behind these remarkable images? What inspired his creative journey? To uncover these answers, we delve into an intimate conversation with Barbieri, tracing his path from the serendipitous beginnings of his career to his rise as a leading figure in fashion photography. He reflects on the influences that shaped his distinctive style, from the playful experiments in his parents' basement to his collaborations with some of the world's most famous magazines.

In this candid interview, Barbieri shares his insights on the evolution of photography, the transition from analog to digital, and the ongoing challenge of balancing artistic vision with commercial realities. His thoughts offer a rare glimpse into the mind of a true master, whose work continues to inspire and captivate.

Join us as we explore the life, work, and enduring legacy of Gian Paolo Barbieri—an artist who has not only captured the essence of fashion but has also defined its visual narrative for generations to come.

Early Beginnings and Influences:

OONA: Mr. Barbieri, can you take us back to the beginning of your journey? What sparked your initial interest in photography?

GIAN PAOLA: I have to say that it is a love affair that began somewhat by accident, almost unconsciously.

When I was a boy, it was just a means that accompanied my fun and that of my friends. It is something that slowly grew on me until photography became my second language, indispensable for giving image to what I could not express with words. I used to experiment with light in the basement of my parents' house with light bulbs placed inside the stove pipes and with fabrics that I "stole" from my father's warehouse, I used to test the light and its effects on the various fabrics that I draped over my friends with whom I used to reenact the scenes from films or plays I loved most. I also had a photography manual that I used only to do the opposite of what it taught. From the stimuli I sought in everything around me, from art to cinema, from literature to theater, from anecdotes and tales of traditions of places I frequented, I built up a cultural background that has allowed me, and still allows me, to experiment with my imagination and make it a reality

OONA: Which artists or photographers influenced you the most in your formative years?

GIAN PAOLO: Avedon, Mapplethorpe e Gauguin.

OONA: How did you make the transition from your early work to becoming a prominent figure in fashion photography?

GIAN PAOLA: Certainly, the pivotal moment occurred in the early 1960s when I started collaborating with the fashion magazines of the time: Pellicce e Moda, Linea Italiana, Novità, which was then acquired by Conde Nast in 1962 and became Vogue Italia. I did the first cover of Vogue Italia with the beautiful Benedetta Barzini.

Benedatta Barzini. Vogue Italia & Novita, Milano 1965

OONA: What was your first significant breakthrough in the fashion industry, and how did it shape your career?

GIAN PAOLO: A defining moment in my life was Diana Vreeland's proposal to go to work for Vogue America. I refused without much hesitation; I was very attached to my homeland and had found a balance that allowed me to take long trips and then always come back. Sometimes, however, I wondered how it would have gone if I had accepted.

Creative Process:

OONA: Can you describe your creative process when conceptualizing a shoot? How do you translate your vision into a tangible photograph?

GIAN PAOLO: My way of working was always the same, I never stopped feeding on art, cinema and literature, which continued to influence my gaze and my thinking.

I used to do research, collect my references and try to make reality what I imagined in my mind. I was drawing my sketches, leaving nothing to chance; I was preparing the set by paying attention to details and only at the end would I take the shot. The creative process, the path that leads you to the shot, is the most important part of photography.

Daniela Ghione, Interview 1986

OONA: How important is collaboration with designers, models, and stylists in achieving the final image?

GIAN PAOLO: The understanding between the players contributing to the success of the shot is fundamental. This used to be much simpler; the relationship that was established between the photographer and the stylist was much stronger and the same was true for the models. There was a relationship of greater complicity and the photographer had greater freedom of expression, less constrained by the presence of multiple players.

Technical Mastery:

OONA: Your work is known for its technical precision. How have you seen the evolution of photographic technology impact your work over the years?

GIAN PAOLO: Certainly, there has been a drastic change from the analog to the digital system: on one hand, taking photographs has become much simpler, but on the other hand, there has been a loss of the poetry that existed with film negatives. The immediacy of snapping a shot and the frenzy of production have caused a loss of connection and awareness between the photographer and the portrayed subject. Today, there is more focus on post-production than on pre-production.

My approach has always been the same: I view photography as a cultural phenomenon. It must reflect beauty because, as the Greeks said, where beauty is born, reason is born. Photography must seduce and attract. This is the most important definition that photography should have. I go by instinct. The work of a photographer is a work of visual arts. As far as I'm concerned, I've drawn a lot from sculpture, painting, and especially cinema. These arts have shaped my view on composition, style, and light. American film noir from the 1940s and Italian Neorealism have been significant for me. Then there is the memory that transmits, engraves, and brings forth everything you have studied or observed at the moment of creation.

Valentino Garavani, Roma 1969

OONA: What are some of the technical challenges you’ve faced, and how have you overcome them?

GIAN PAOLO:I had mastered the technique I had acquired as a self-taught photographer; what today is done with post-production, I used to do with my own hands. I had no problem rolling up my sleeves and creating with whatever I had at my disposal.

Certainly, experimenting and transitioning to digital was initially a complicated step coming from another generation. But once I understood how it worked, I recognized that in some cases it speeds up the process and reduces costs.

Iconic Projects and Campaigns:

OONA: You have been behind some of the most iconic fashion campaigns and editorial spreads. Which projects stand out to you as particularly memorable or transformative?

GIAN PAOLO: One of the most memorable and provocative shoots was in 1974 in Rome for Valentino. I decided to draw inspiration from Jodorowsky's The Holy Mountain, one of the most radical and visionary movies ever made. Each image was meticulously crafted, with the kind of alchemical power I strive for in my work. I aimed to transpose the imagery from that film into my photographs. Some of the shots were taken inside a church, where the model Susan Moncur played Mary, and another model took on the role of Jesus. At one point, a nun entered the church and, upon seeing the half-naked models smoking, exclaimed, "No smoking in church!"

There’s a particular shot where Susan Moncur, again as Mary, is lying on the bed with a Playgirl magazine between her legs, while Jesus is making his entrance through the door. That photo wasn’t published because it was deemed too racy.

Susan Moncur in Valentino, Vogue Italia, Roma 1976

OONA: Can you share any behind-the-scenes stories from one of your most famous shoots?

GIAN PAOLO: Certainly, the shoot I did in Port Sudan for Vogue France in 1974 deserves to be told. I was looking for inspiration and remembered a scene from a film where Marlene Dietrich, looking elegant, was traveling along a tropical port in a carriage. I thought about acquiring a rhinoceros to be hung from a crane, with Marlene Dietrich observing, but it proved impossible to find a rhinoceros, so I opted for a camel instead. We climbed up a very precarious fire escape to reach the roof of a warehouse. From there, I could see the entire port. The situation was very unstable because the roof was steeply pitched, made of asbestos, and scorching under the sun.

Adnan Khashoggi, one of the most powerful men in the world, had hosted us and kindly halted all port traffic to allow a crane to position itself in front of the warehouse and lift about twenty meters. I positioned the model, and the camel was raised to my height. However, the owner kept saying that the camel couldn’t stay hanging like that or it would die, and he kept lowering it. There was a constant “up and down” as I had to keep paying 20 dollars each time to raise it again. I faced a lot of difficulty because when the camel reached my height, it was never in the right position. The model was precariously seated on the roof, and the camel kept presenting its rear end to me.

The level of difficulty, the great creativity, teamwork, and the professionalism of the model all contributed to the success of the image—elements that have accompanied me throughout my career.

Monica Bellucci in Dolce & Gabbana, Milano 2000

OONA: What model would you work again and who would you never work with?

GIAN PAOLO:I would definitely work with Ivana Bastianello, Alberta Tiburzi, Ingmari Lamy, basically with all my muses who are still present in my life. I would not work again with Sharon Stone.

Alberta Tiburzi, Milano 1967

Artistic Vision:

OONA: Your photographs often evoke a strong narrative and emotional depth. How do you infuse storytelling into your images?

GIAN PAOLO: Art in all its forms has always been the element that has allowed me to live and survive. Since childhood, every inspiration I found from visiting exhibitions, reading art history books, or simply walking around Milan was a window to another world that allowed me to learn and create. I used to visit Galleria Vittorio Emanuele and buy postcards of famous paintings, which I would use as inspiration for my drawings. I then sold these drawings in the summer in Santa Margherita Ligure to make some money.

I would draw inspiration from figures and colors, which I then tried to bring into my photography. I particularly love painting and have experimented with it myself, with Gauguin's style being the one I have always been most passionate about.

In photography, I tried to mimic the effect of oil painting by applying Vaseline to the lens. I often painted the sets myself, creating real environments that would evoke a specific painting or the style of a painter I admire. For instance, in the 1998 campaign for Vivienne Westwood, one shot depicted a girl sitting inside a room reminiscent of a Matisse painting.

OONA: How do you balance commercial demands with your artistic vision?

GIAN PAOLO: In the early years of my career, my creativity had free rein, and at the same time, fashion was emerging and the market that would support it was taking shape. Among photographers and designers, relationships were built first on friendship and then on commercial interests. We loved creating together, laying the foundations for what is now known as the fashion system. It was a time of fun and happiness.

Gradually, however, creativity was pushed to the background, and the number of people involved in a shoot increased: art directors, fashion editors, photo editors, etc. This made the fashion system increasingly a purely commercial mechanism.

Felicitas Boch, Milano 1982

Legacy and Impact:

OONA: Reflecting on your extensive career, what do you believe has been your most significant contribution to the world of photography?

GIAN PAOLA: To restore to women and their role within society the recognition they deserve.

OONA: How do you hope your work will influence future generations of photographers?

GIAN OAOLO: I only wish that my work really becomes an inspiration to someone and that the archive remains one of those links that will bind new generations to a time when the perception of the world was different, less ephemeral than now, and with it the way of conceiving photography, with another flavor and depth.

I hope that the importance of culture, a recurring theme in my work, remains evident to those who wish to pursue photography.

Personal Insights:

OONA: How has your personal journey and experiences shaped your work and your approach to photography?

GIAN PAOLO: Every time for me is a new beginning. It’s like being asked to tell a fantastical story. For me, each time means projecting my imagination and turning it into reality, blending it with the collection of ideas in my mind. The carousel of inspirations, carefully gathered throughout my life, comes together to create a unique narrative each time.

OONA: What advice would you give to aspiring photographers who look up to you and want to follow in your footsteps?

GIAN PAOLO: Follow your passions and never stop believing in them. Experience is the main driving force, as is culture. Times have changed, and a photographer’s portfolio is becoming increasingly important as we approach market saturation. But above all, it's crucial to have a clear sense of oneself. It's essential to know and listen to yourself to present yourself in the most genuine way possible.

The Evolution of Fashion Photography:

OONA: Fashion photography has evolved significantly over the decades. How have you adapted to these changes while maintaining your unique style?

GIAN PAOLO: Fashion photography once had a cultural depth that I find hard to find in today's evolution. Photographs are now so retouched that they lose their authenticity; legs are elongated, skin is smoothed to the point of losing texture, and women start to look alike. In the past, imperfections could be corrected with manual retouching, but digital technology now allows for a complete rewrite of the image.

I still believe that photography is an art for a few. It’s not enough to know how to use a camera, position a light, or use Photoshop to achieve a great shot. It’s something that goes beyond these technical aspects. It’s a love that comes from the mind and body, brought to light with technical tools. The digital process has removed creative steps that were once crucial for perfecting a set: poses were prepared with sketches, inspiration was drawn from cultural backgrounds, and nothing was left to chance. With digital technology, much of this has become somewhat superfluous.

Susan Robinson in Walter Albini, Portofino 1972

OONA: What trends in contemporary fashion photography do you find most intriguing or promising?

GIAN PAOLO: It's hard to say. Today, social networks are mainly used to reach the masses, where visibility lasts only a few seconds. If your work can't capture attention in that tiny window of time, you’re lost. On the other hand, I believe there is a lot of talent that needs to be promoted, and the trend that intrigues me the most is the combination of art and technology.

OONA: How do you feel about the digitalization of the images and modern day photo shop and AI?

GIAN PAOLO: What's important is that the language is used to communicate something. If photography doesn't convey a message, it serves no purpose, whether it's taken with a cellphone or created with AI.

Future Endavors:

OONA: What are your current projects or upcoming ventures that you are excited about?

GIAN PAOLO: One of the projects that excites me the most is the collaboration with 24 Ore Cultura. They are working to showcase my work abroad, generating interest in museums across major European cities and eventually expanding to the rest of the world.

OONA:How do you envision the future of photography, both as an art form and an industry?

GIAN PAOLO: Photography will never die; it will regain its strength. It’s essential to revisit its essence and start from there.

Susan Robinson in Walter Albini, Portofino 1972

Philosophical Reflections:

OONA: Photography is often described as a medium that captures the essence of a moment. How do you interpret this idea in your work?

GIAN PAOLO: I have always believed that photography encompasses more than just the essence of a moment. While the moment itself is certainly captured, the journey leading up to that moment must be just as discernible, as well as the path that follows.

OONA: If you could photograph any moment in history, real or imagined, what would it be and why?

I would love to accompany Gauguin to Tahiti, to experience those lands with him and document those wonderful, and still untouched people.

Final Thoughts:

OONA: What legacy do you hope to leave behind in the world of photography?

GIAN PAOLO: As I mentioned earlier, I hope that my archive can serve as a tool for research, knowledge, and memory of a time that no longer exists.

OONA: How would you like to be remembered, both as an artist and as an individual?

GIAN PAOLO: Just like what has come over time and has left an imprint.

Interview by Oona Chanel

Images by Gian Paolo Barbieri

Rankin's Lens - Rediscovering Cool Britannia in 'Back in the Dazed

Author Magazine Editor-in-Chief Oona Chanel sits down for an exclusive interview with legendary photographer Rankin, whose work has not only captured but also redefined the essence of the 90s British cultural landscape. In this intimate conversation, we delve into the narratives, social commentary, and political undertones of Rankin’s photography, beautifully showcased in his retrospective, "Back in the Dazed." This exhibition at 180 Studios offers a nostalgic journey back to the heyday of Cool Britannia and 90s style—an era immortalized through Rankin’s visionary lens. From cult celebrities and musical icons to supermodels, Rankin was at the heart of London's cultural revolution. His work with Dazed & Confused didn’t just reflect the zeitgeist; it actively shaped it, giving voice and vision to an entire generation.

“As a photographer, I feel a deep responsibility to consider the impact of my images. My approach has always been to provoke thought and push boundaries respectfully. Plus I’ve always used photography to turn a critical eye on culture and critique society. For me, the nature of media, and the medium of image creation and dissemination, is a discussion we can’t afford not to be having.” - Rankin

OONA: In 'Back in the Dazed,' you revisit the iconic era of Cool Britannia and 90's style, which you captured so vividly through your lens. How do you perceive the cultural and artistic impact of this period on contemporary British identity, and what do you hope viewers take away from this retrospective exhibition?

RANKIN: Large part of why Creativity in the 90s was so interesting was because we were all the younger brothers and sisters of punks. That DIY attitude was just embedded into us from a young age.

So we all had an attitude of wanting to do it our way. This irreverence was kind of baked into us all and it really influenced our approach to our work and lives. It definitely gave me a confidence in myself that was kind of unshakeable.

Helena Christensen

Helen Mirren

In fact the main reason Jefferson and I started Dazed & Confused was because we wanted to control the medium we were working in. We didn’t want to work for someone else and we set out to change what a magazine was and what it could do.

The show tells that story through the medium of photography. It's like watching me grow up as a photographer and watching a set of kids experiment and push the boundaries of what a magazine and its content could be!

OONA: Your work with Dazed & Confused Magazine not only documented but also shaped the aesthetic of a generation. Could you discuss the narrative techniques you employ in your photography to convey the stories and ethos of British youth culture during the 90s?

RANKIN: When I look back now, I wish I’d done more documentation of the period, just good clean photos not only concepts. I’d just love to have those images. What I ended up doing was really trying to combine conceptual photography and the seduction of fashion. I was trying to put ideas into every picture.

Some of that was great, some didn’t work. I was also obsessed with breaking the rules of fashion and beauty and showing things could be done differently.

When you look at the work in the show through that lens, you can see we predated a lot of the imagery that we all take for granted now; specifically around representation and equity. Those early years were definitely great for experimentation and starting out, I was like a blank canvas. We were naively fearless, doing things that inevitably changed culture.

OONA: The 90s were a time of significant social and political change in the UK. How did these broader contexts influence your work, and in what ways do you see 'Back in the Dazed' as a political statement communicated through your photographic lens?

RANKIN: I was definitely influenced by what was going on around me and I would always say we were political, even if it was just a small p. body politics, social equity. That kind of thing. But we were also just kids making a magazine straight out of the student union.

At college we literally did every single part of that magazine. We financed a lot of the earlier issues by doing parties, because we got into the club scene, and that really was the making of us. I think that our student experience made us realise that we could do it on our own. When we started Dazed & Confused there was a massive recession in Britain. Thatcher’s policies promoted an underground economy, encouraging small, underground businesses. That Do-It-Yourself spirit coupled with a few sponsorships helped us get a leg up.

OONA: As 'Back in the Dazed' is the first retrospective of your groundbreaking works over this prescient decade, how do you reflect on your artistic evolution during these years? What key moments or images stand out to you as particularly transformative or indicative of your growth as an artist?

RANKIN: From those Dazed years, I would say that the series “Blow Up”, was really the first pivotal piece of work I did and it really stays with me. The idea was to create a portrait of nightlife at that time by taking pictures of clubbers at nights all over London. It was a baptism of fire in many ways as I was shooting in these pop-up environments, and it’s all real members of the public with their own distinct personalities. How to photograph fast and build real rapport quickly was so important to learn and I’ve kept and honed those skills over the decades since. In a lot of ways this was the first iteration of my RankinLIVE project, which I still do today, where I take pictures of the public, not models or celebrities.

Jude Law

RANKIN: When it comes to celebrities, Björk was the first serious musical artist that I photographed. We’d been doing the magazine for only a couple of issues when we got the call from her record company, saying that she would like me to do a press session. This was the first time a celebrity had paid me for a shoot, so I was seriously nervous. As a way to protect myself, I took Björk to St. Albans, where I’d spent my teenage years as there was a comfort in the known.

Björk was an amazing collaborator and quite graciously guided me if my inexperience showed. She made me realise that I should always follow my own instincts and not be derivative. That way of working set the blueprint for how I approached every portrait shoot since.,

Nanu Nanu Björk

OONA: Your lens captured a myriad of cult celebrities and musical icons, each contributing to the fabric of 90's British culture. How did your approach to photographing these figures evolve, and what insights can you share about the symbiotic relationship between your subjects and the cultural zeitgeist they helped define?

RANKIN: I get asked a lot to define the “Rankin style”, I think people expect me to recommend a light or talk about always shooting in a studio. But I always thought that was a bit of a cop out. I don’t think my style is really aesthetic, it’s about how I interact with the people I’m photographing. I’m a collaborator and I want every image to be of the person, people should look at them, not just look at my style.

I think the 90s was a time where that level of honesty was key. We talk about authenticity now with celebrities, but we were doing that 30 years ago. I wanted people to open up the magazine and feel a connection with the people on the pages, just like Liam and Noel were putting out songs which kids could feel some kind of emotional or rebellious resonance with. It was real, that's the key.

U2

Minnie Driver, Debbie Harry, Michael Stipe

OONA: Throughout the decade covered by 'Back in the Dazed,' you produced over 200 iconic editorial shoots. Can you elaborate on your creative process and methodology during these shoots, and how you managed to consistently capture the essence of the era?

RANKIN: I didn’t grow up in the art or fashion world. I’m from a working-class environment and that means I’ve always considered myself an outsider looking into the industry. I’m lucky though, my parents always encouraged me to ask questions, to not settle, and that turned me into a bit of a contrarian. This background means, although it's my craft and passion, I haven’t had to take everything so seriously in photography. I never needed to preserve the status quo in the industry. My shoots can be humorous, or pointed, conceptual or emotional, they can be anything I want them to be. I think this is why, looking at the exhibition, you get a sense of the decade. I’m not doing the expected, I’m shooting models and real people, kids on the street as much as high-culture. So there is more than surface, there is an attitude which feels representative of the time.

OONA: Given that 'Back in the Dazed' revisits a period that continues to influence contemporary aesthetics and culture, how do you view your legacy within the realm of fashion and portrait photography? What aspects of your work from the 90s do you see as most relevant or resonant with today's artistic and cultural landscape?

RANKIN: I hope a lot of the work still feels quite fresh and modern. But the part of my work that I think still resonates is the stuff where I was very much going up against a lot of the other things that were homogenous within the industry. I photographed plus sized models, had older women in shoots, the first cover for Dazed was an openly gay black man - these things are common now and everyone’s shouting about inroads which are being made in representation but we did lots of these things in your face first.

Charlie Watts

David Thewlis

OONA: The design and curation of an exhibition play crucial roles in how audiences engage with the work. Can you discuss the curatorial choices made for 'Back in the Dazed' and how these decisions enhance the viewer’s experience and understanding of the cultural significance of your photographs?

RANKIN: I work with a curator, Ellen Stone, so I’ve asked her to answer this question.

Ellen: When looking at Rankin’s work the term “authenticity” comes up regularly. There is an emotional authenticity and a conceptual authenticity to his images, so I wanted to find a match to that within the curation. By arranging the photographs in chronological order, the design of the show allows viewers to experience the evolution of Rankin's work and the cultural shifts of the 90s and early 2000s as they occurred. This approach helps the audience appreciate the progression and changes in style, mood, and societal trends authentically, capturing the true essence of the era without the need for large amounts of texts explaining each image. Instead we went for encouraging direct and personal engagement with the visuals, while the comprehensive timeline at the end provides deeper context, reinforcing the temporal authenticity of the exhibition.

In the end though, it’s a show about finding your own connection to the imagery and I really hope the paired back aesthetic gives everyone space to find themselves in the imagery.

Edward Enninful

Ewen Bremner

OONA: Your work often transcends mere documentation, offering a manifesto on how to view the world. Could you delve into the philosophical underpinnings of your photography during the Dazed & Confused era, and how you aimed to communicate broader truths or critiques through your images?

RANKIN: I realized early on that photography is a powerful medium. All of it from documentary to fashion. It shapes societal views and can define or challenge cultural norms. As a photographer, I feel a deep responsibility to consider the impact of my images. My approach has always been to provoke thought and push boundaries respectfully. Plus I’ve always used photography to turn a critical eye on culture and critique society. For me, the nature of media, and the medium of image creation and dissemination, is a discussion we can’t afford not to be having. Especially now.

Back then I think you see that even as a baby photographer I was exploring these themes and trying to find a voice to discuss them. 30 years ago I was doing shoots about the fashion industry’s mistreatment of models, and was trying to find new ways to depict emotions. Some of my favourite shoots were conceptual and the aim was to critique not accept the status quo.

Katie Grand

OONA: The creative community that emerged around Dazed & Confused Magazine was vibrant and influential. How did collaborations within this community shape your work, and what role do you believe such creative collectives play in fostering artistic innovation and cultural shifts?

RANKIN: Dazed was born out of collaboration. None of us had ever done a magazine before, we were all pretty new to it. But I think the energy was really optimistic, and we were also really competitive.

The thing that really kept it fresh, was the team's internal competition to do work that got given pages. That tension and jeopardy made all of us very inspired. We definitely pushed each other to do better work, even if it was more about trying to get more space in the magazines. From styling to glam or editorial, we were making it up as we went along, and somehow that hard work paid off. I can look round the publishing, fashion and beauty industries today and those people I came up with are not the top players.

Looking back I only wish I’d appreciated it more at the time. They pushed me to be a better photographer and I owe them everything for that.

Tilda Swinton, Ben Daniels

‘Back In the Dazed: Rankin 1991-2001’ celebrates standout imagery from over 200 editorial shoots by Rankin for his magazine Dazed & Confused. On display until July 7th at 180 Studios, London. Tickets are available at 180studios.com/rankin.

Interview By Oona Chanel

Images By Rankin

MILES ALDRIDGE - Imperfect Beauty

The Legendary Photographer On Discovering The Art Of The Lost Moment

There are few photographers working today whose body of work is instantly recognizable, but Miles Aldridge has made memorability his signature. His subversive pop art scenes of hypnagogic color-soaked cinematic perfection contain an elusive aesthetic quality that runs through every image like an enigmatic signature, one that has been busily deconstructing notions of female beauty and the malegazeforthepast20years. His recent book, P leaseReturnPolaroid(Steidl), marked a radical departure from carefully staged and executed image-making, providing a glimpse into an unintentional and instinctual realm of the subconscious, where the genesis of his images actually takes place. In this extract from an extended interview in AUTHOR, he tells us why a love affair with disruption, decay, and destruction has revealed the beautiful imperfection of his inner life.

AUTHOR:What did you discover looking at the Polaroids that you felt you had never seen or realized before?

Miles -I started to nd pictures that I didn’t understand, even though I had taken them. I mean, there were pictures where I had taken a Polaroid of space before the models were placed in it, just so I could see the light and the strangeness of this empty scene, and it feels almost like a crime scene because of the attention that my camera and my light has created. There are many shots like that, where they are empty of the model and the scene becomes very pregnant and poignant with meaning. That is why, in a way, they feel appropriate, because I took them but I don’t remember taking them. I’ve found these images that are mesmerizing and intriguing to me, not because of the image I was trying to take, but because of accidental things, such as the model not being there or some damage to the image... I became really interested in creating a series of these that come together in a kind of Lynchian dream narrative.

AUTHOR: There is a sense of intense beauty precisely because of their imperfections.

Miles -I think there is always an attraction to things that are cracked or ruined or broken. What that is, I don’t know, but I think a concrete floor can be quite beautiful, but if it has a crack in it, then it

can be even more beautiful. The crack draws us into thoughts about our own mortality and as much as we want to be fabulous, we are not. The crack in the pavement, the tear in the canvas, and the smear of the pain, are all truthful marks that underpin this idea that we are not immaculate God-like creatures, we are all awed like the deeply human characters Shakespeare depicted in his plays.

AUTHOR:It’s the passing of time that is beautiful, the melancholia – to paraphrase Shakespeare’s Richard II, let us make dust out paper and with rainy eyes write sorrow upon the bosom of the earth...

Miles -Beautiful. Yes, it’s all about the beauty that has passed. You know, I was so drawn to these awed scratched and wrecked images because I think, coming after I Only Want You To Love Me, where I had presented a kind of Technicolor universe; this represented the other side of the coin. This was the director’s script with all the continuity notes. It’s interesting for me how much I’ve enjoyed seeing these images, and the question for me now is, do I continue with the kind of Technicolour perfectionism, or can some of this accidental damage, disruption, and decay become instilled in the final images? I think the answer is yes, it can.

Interview by JOHN-PAUL PRYOR ,

Pictures by Miles Aldridge

What is happening in Lebanon?