Moonsoon: Zaha Hadid’s First Major Completed Work Abroad

Dame Zaha Hadid is undoubtedly one of the world's most-known architects. And while her prominence is predominantly rooted in architecture through internationally acclaimed works, such as Al Janou Stadium for the 2022 World Cup, Dubai Opera House and London Aquatics Centre, her first completed international commission was an interior design project in Sapporo, Japan. Based on a series of previously unrealised works in Japan, The Moonsoon Bar and Restaurant was commissioned by Michihiro Kuzuwa of JASMAC in 1989 and was completed in 1990. Influenced by everything from the works of Alexander Calder to photocopies of orange peels, the interior acted as an eclectic visceral representation of hybridity and playfulness. But most importantly, this project laid the foundation for design sensibilities seen in Hadid’s later work. Held until 22 July 2023 at The Zaha Hadid Foundation in London, Zaha’s Moonsoon: An Interior in Japan exhibition gave Author a chance to sit down with its curator Johan Deurell. We touched on the significance of the Moonsoon work in the wider Zaha Hadid canon, the prevalent design elements, and the influences behind this project, as well as her unique ability to work across several disciplines.

“Zaha was such a polymath. She could have ended up doing any kind of creative [work], it just happened to be architecture.”

Philip: What's your background in terms of curating exhibitions?

Johan – After graduating with my MA in History of Design from the Royal College of Art, I worked as a freelance art critic and curator, as well as an associate lecturer at Central Saint Martins for a number of years. However, in early 2018, I joined the Röhhska Museum of Design and Craft in Gothenburg where I worked for four and a half years and curated several shows. When I joined, we did a whole rebranding and revisioning project for the museum; I wanted to join because it was kind of a traditional museum with a lot of potential.

Philip: I suppose it was an opportunity to implement your vision within the wider framework?

Johan – It was exactly that. The director of the museum, Nina Due, really wanted it to be a Contemporary Design Museum [while] also engaging with critical dialogues in the field and making it a bit more relevant. I think was also about my take on design. I'm more interested in what people call critical design or conceptual design rather than standard product design.

Philip: I'm quite curious, how did the relationship with Röhhska then transform into working for the Zaha Hadid Foundation?

Johan – I was excited about the Foundation because it's quite nice to join a completely new organisation. You have a sense of shaping it.

Philip: Yes, I can see a theme there — you want to work with and implement new ideas while shaping and taking them in a certain direction.

Johan – Exactly. With an archive-based show like Moonsoon, that's one part of it. I wouldn't say that fits into the kind of curatorial projects I have done in the past because they've all been linked to current political issues, whereas this is about design in a historical context – the Japanese Bubble Economy. The contemporary programme we’re launching in the future is very much more typical for my curating as it engages with ideas of hybridity, exchange and the built environment.

Philip: My question to you is: Why Moonsoon? What was the impetus to focus on this particular work?

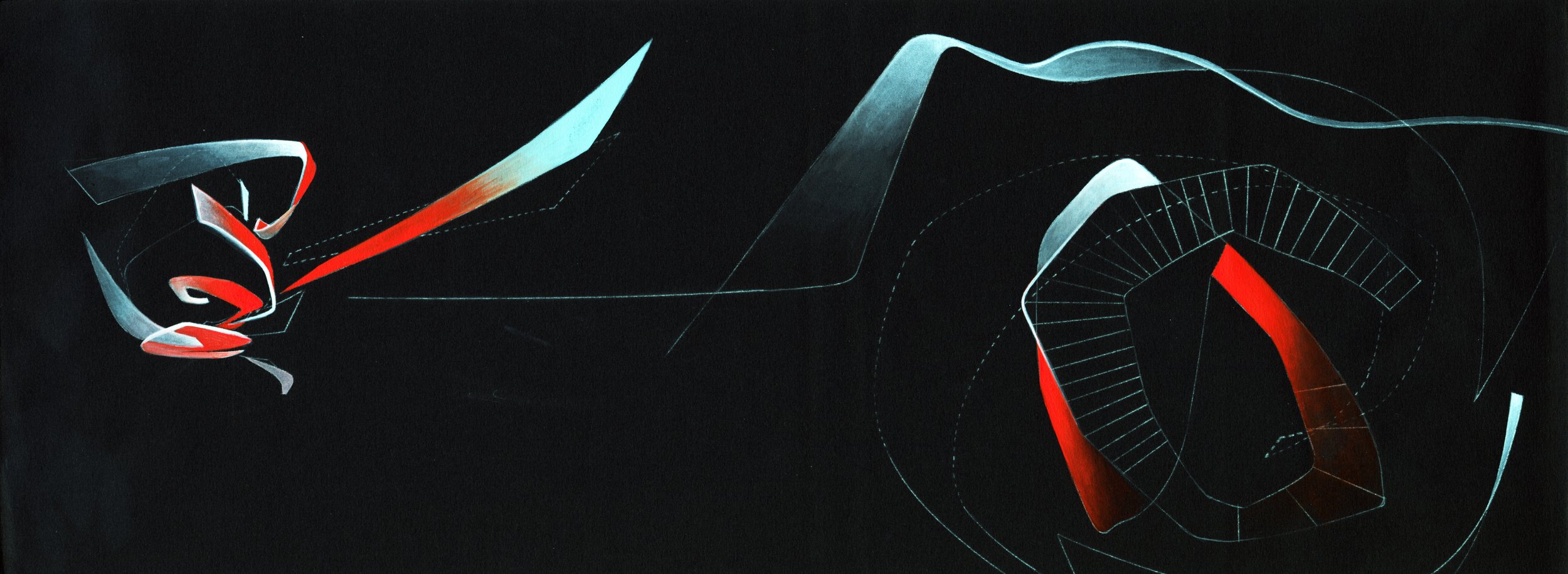

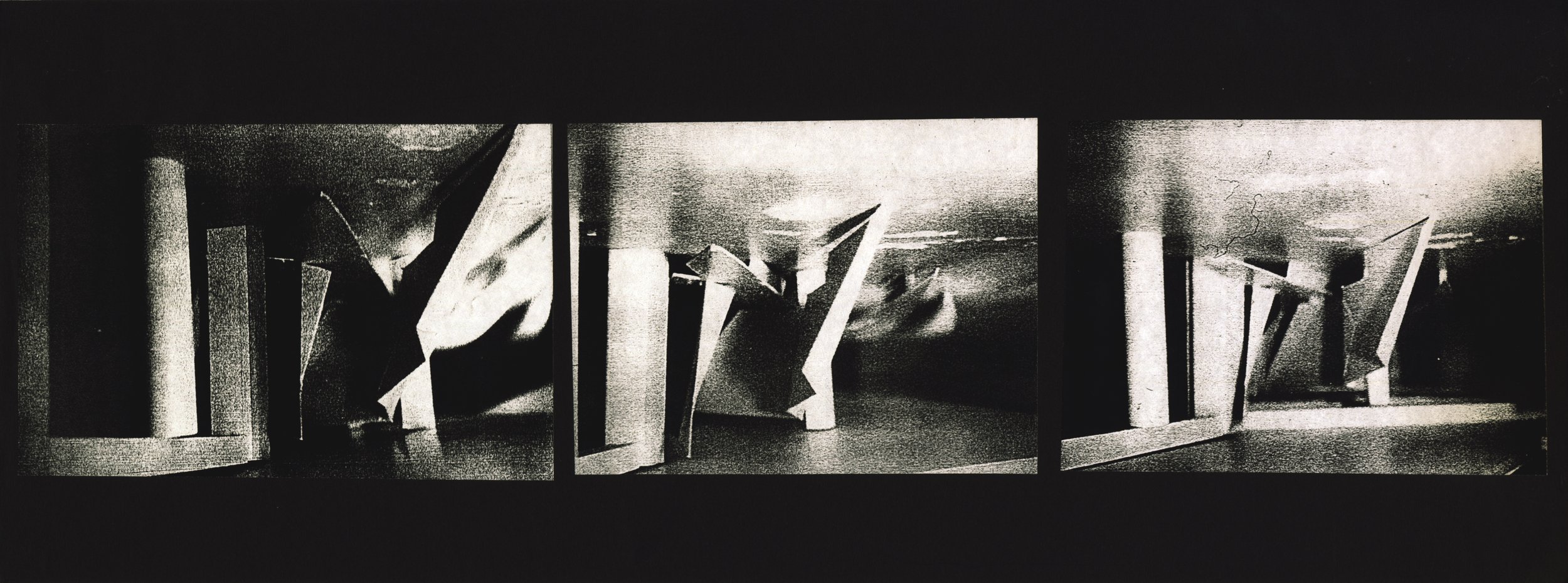

Johan – There were several reasons. I was attracted to it on a purely visual basis. But I think it's important [for it] to be studied as part of the Zaha Hadid canon because it's her first major interior and the first project to be completed outside of the UK. It's the first time we get a sense of what a Zaha building might have looked like. Before this, she had only done paper-based architectural projects with the most publicised one being the Peak Project in Hong Kong from ‘83, exhibited at the Deconstructivist Architecture exhibition in MoMA in ‘88. In those earlier projects, Zaha Hadid Architects developed design strategies such as the layering or warping of shapes, the oblique nature of those shapes, and the embrace of all angles — those ideas established the early design language for the practice. I see Moonsoon as a blueprint for later architectural projects.

Philip: Were the interiors, especially the furniture, made by Zaha Hadid Architects or were they commissioned externally?

Johan – They were made by Zaha Hadid Architects. It's a practice with several people contributing, although in the ‘80s there weren't that many. Michael Wolfson, who was employed by Zaha, designed the sofas that were part of the seating landscape, but several people contributed to the various elements of the project. This included the interior, the architectural elements, and interventions such as the orange peel vortex and the black swirl going through the two floors.

Philip: What were some of the founding principles she based this work on?

Johan – The Kita Club building, built by Dan Sekkei Architects and Mitsuru Kaneko in the late ‘80s, contained a sort of dome which Zaha didn't like. So the orange peel was a design intervention. The vortex was a central theme in the design of the building. I saw it as a leading visual key, connecting all the objects and the exhibition. I interviewed the various architects who worked on the project, and they kept saying, “You need to find a Post-it note or sketch or something with little doodles.” In this case, it turned out to be a sheet with an Arabic letter. I wanted Marwan [Kaabour] to work on this as a graphic designer as I wanted to construct a slideshow to link it with that shape. He speaks Arabic and says that this swirly shape reflected a stylized version of the letter H in Zaha. But there were also a lot of other interesting references: Photocopies of books, orange peels in the photocopier, and works by Alexander Calder — loads of different works that had a similar shape.

Philip: Yes, it’s interesting you mention Calder because when you look at her work, you see the likes of Malevich, Calder, and Lissitzky having a huge influence on her.

Johan – Yeah, I agree. One of the reference images that we found was the Aula Magna of the Central University of Venezuela, designed by Alexander Calder. It has these typical Calder shapes for absorbing sound in the ceiling. And if you look at them — the sofa, the sofa’s backrest, and the tables — they look like elements from Calder’s “Mobile.” Her design language is heavily influenced by Malevich and the Russian Constructivists. In the early projects, she sort of translated that into architectural design strategies. And Zaha, as an architect, was very visual. And you see all these visual sources and how they come together.

Philip: Yes, she was incredibly visual and influenced by fashion in her design practice, especially the likes of Comme des Garçons and Issey Miyake. Would you be able to tell me more about that?

Johan – That's a research project we are going to undertake in the future. We have a large fashion collection in our archive, including clothes, bags, shoes, and jewellery by several big designers. We know that fashion was important to her; she paid a great deal of attention to it. Zaha made her own clothes when she was a student. Wolfson told me that Zaha was such a polymath, she could have ended up doing any kind of creative [work], it just happened to be architecture. I found some evidence of how fashion influenced her work, which I haven't had time to research properly. She did this project for Pet Shop Boys and designed the sets for their world tour in 1999. There’s a mood board for that project that contained some pleated Issey Miyake pieces.

Philip: Zaha Hadid had her fingers in almost every possible pie; she was an architect, a designer, and a painter. Will the foundation have a look at Hadid's larger body of work at some point?

Johan – We will. And that’s also why I found the prospect of [working for] this foundation interesting because I'm interested in interdisciplinary practices. What makes her so interesting is that she moved and operated within these fields. But it’s also about connecting the dots between her work within these different disciplines.

Philip: These are the type of things the foundation is such a vast source for. You have such a large archive to work with.

Johan – I’m super excited about the fashion-slash-Zaha relationship and would love to make that into a separate, large-scale exhibition for an international tour in a couple of years. It is interesting to depart from our archive to look at ways in which fashion and architecture intersect and feed into one another.

CREDITS

Interview by Philip Livchitz

Pictures by Zuzanna Blur